Vision

Liveable, water sensitive and climate ready communities supporting natural healthy and connected landscapes

Introduction

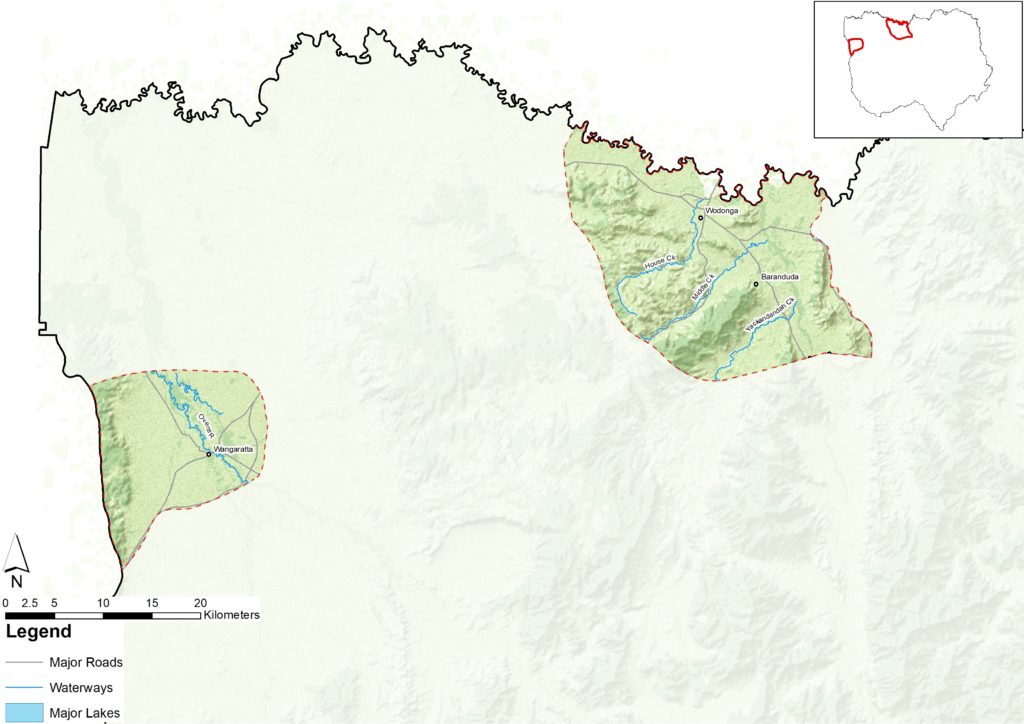

Shown on the map as two distinct areas, this landscape is home to the regional centres of Wodonga and Wangaratta.

The Victorian Government identifies Wodonga and Wangaratta as places of significant growth and development. These highly modified landscapes still host a range of iconic natural features including the Ovens, King and Kiewa Rivers and forested parks.

This landscape is significant for Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples for traditional and contemporary reasons. Many cultural heritage sites have been lost due to development, but storylines remain, and Wodonga is home to a strong and thriving Aboriginal population.

Notable features of the Wangaratta portion of this landscape are the carpet python, Warby Range swamp gum and presence of springs and waterfalls. The Ovens River that runs through Wangaratta is the only unregulated tributary of the Murray River.

What is important?

Important attributes

Important attributes of this landscape identified by those who live, work, visit or connect with this landscape include:

- Vegetated corridors along waterways, paths, roads and in public spaces providing connected habitat and natural spaces for recreation and relaxation

- Clean accessible waterways and wetlands

- A balance between urban development and natural areas, with protection of important natural areas such as Wodonga Hills and strategic agricultural land

- Liveable urban environments with green spaces, shade and good connection between open spaces

- Expanding industries providing broad range of employment opportunities

- Sustainability in water sensitive urban design.

Key features

| Theme | Key features |

|---|---|

| Land | Features the two large urban regional centres of Wodonga and Wangaratta. Urban and peri urban areas include large woodland reserves, rural properties, waterways and riparian reserves and scattered large old trees. Wodonga is an urban centre at the foothills of Great Dividing Range with greenbelts, open spaces and protected hill tops. River Red Gum forests surround the peri urban landscape of Wangaratta. Various public land uses include formal parks, informal parks, riparian reserves, rural riparian reserves, habitat reserves and constructed floodways. Strategic agricultural land of significance adjacent to both peri urban areas of Wangaratta and Wodonga. |

| Water | Heritage-listed Ovens River joins the King River system at Wangaratta, flowing through the town centre and down to meet the Murray River at Bundalong. Creek systems that flow through Wangaratta’s residential areas are One Mile Creek and Three Mile Creek, both part of the Fifteen Mile Creek system. The Murray River, Kiewa River and Lake Hume are priority waterways that border Wodonga. Priority creeks within the Wodonga area are Castle Creek, Felltimber Creek, House Creek, Huon Creek, Jack in the Box Creek, Kookaburra Creek, Middle Creek, Wodonga Creek, Finns Creek, the Kiewa River and Yackandandah Creek. The Mullinmur Wetland at Wangaratta is an important ecosystem under environmental management. |

| Biodiversity | A range of riparian habitats surround Wangaratta and Wodonga. Seasonal wetlands and sites such as Wodonga Hills play an important role in connectivity and habitat for native fauna and flora. Some important species and communities that are significant to this landscape include: Flora: Box Gum grassy woodlands and large strands of common reed (Phragmites australis) exist in and around these urban landscapes Warby Range swamp gum (Eucalyptus cadens) Seasonal herbaceous wetlands with native grasses and herbs Spur-wing wattle (Acacia triptera) Terrestrial fauna Carpet python (Morelia spilota) Eastern grey kangaroo (Macropus giganteus) Echidna (Tachyglossus aculeatus) Squirrel glider (Petaurus norfolcensis) Woodland birds Brown tree-creeper (Climacteris picumnus victoriae) Speckled warbler (Chthonicola sagitta) Diamond firetail (Stagonopleura guttata) Hooded robin (Melanodryas cucullata cucullata) Lace monitor (Varanus varius) Aquatic/riparian/wetland fauna Sloanes’ froglet (Crinia sloanei) Giant bullfrog (Limnodynastes interioris). |

| Community | In 2020 Wodonga’s population was 42,662 and in Wangaratta it was 29,197. Areas of large employment, aggregation of services and a diverse economy. The regional centres support industries including freight, logistics, manufacturing, defence, education, health, business services, major sporting events and arts and culture. The Wodonga hinterland region is increasingly becoming a dormitory region for the town of Wodonga. It shows modest growth, little structural ageing and higher education levels.[48] Both cities have active urban Landcare, sustainability and friends’ groups. The landscape is significant for Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples for traditional and contemporary reasons. Many cultural heritage sites have been lost due to development, but storylines remain and Wodonga is home to a strong and thriving Aboriginal population. |

Condition

The following is a snapshot of condition for the Urban and Peri Urban Landscape.

| Land | Highly modified due to urbanisation. A significant portion of the land is covered with hard impervious surfaces and development and urbanisation continues throughout the landscape. Wodonga’s urban area occupies around 2,400 ha (with an average population density of 13 people/ha). Wangaratta’s urban centre occupies around 1,500 ha (with an average population density of 11 people/ha). Urban reserves and parks exist throughout the urban landscape and along waterways that are cared for and maintained. Many rural riparian areas are subject to grazing and bank instability issues. |

| Water | Increase in appreciation of the aesthetic and environmental values of urban waterways, has resulted in actions in both Wangaratta and Wodonga to improve the condition of and access to these waterways. Bare hills surrounding Wodonga contributes to increase sediment loads transferring into waterways following intense rain events. Most waterways are in moderate condition and instream woody debris is severely depleted in most rivers. Development has resulted in the loss of many wetlands. Water was delivered to the Mullinmur Wetland for the first time in 2019, to prepare habitat for threatened aquatic species. One Mile Creek and Three Mile Creek, both part of the Fifteen Mile Creek system, pose the greatest flood risk to the city of Wangaratta. Regular testing for emerging contaminants e.g. PFAS testing around Wangaratta and Wodonga has shown results well below the Australian Drinking Water Guidelines, broader impacts in urban areas are yet to be determined. |

| Biodiversity | Highly modified due to urbanisation, with pockets of fragmented native vegetation remaining. Grassy woodland ecological communities are threatened. These ecological communities, including box-gum, grey-box and buloke woodlands provide habitat to a variety of woodland-dependent species in decline. The Warby Range swamp gum (Eucalyptus cadens) is a threatened species endemic to north east Victoria. The highly aggressive and territorial noisy miner (Manorina melanocephala) is impacting on bird diversity across the landscape. The area of cover of native vegetation has not increased significantly in recent years, however the quality of the vegetation is improving with priority works in riparian areas, woody weed removal and vegetating new areas where development is occurring.[49] |

| Community | High employment growth in health and education industries occurring in Wodonga and Wangaratta. Textiles and clothing manufacture which has been one of the defining industries for Wangaratta has declined and is unlikely to generate significant employment growth or development in the future. Overall community interest and participation in events associated with urban landcare, sustainability and friends’ groups are increasing. Increased usage of open green spaces within the urban environments and increased local government focus on improving these spaces. Wodonga Urban Landcare Network actively supports stewardship and land management activities. The network comprises 16 active urban landcare groups. Wangaratta also has an active Landcare and Sustainability group. Wodonga continues to be the fastest growing major growth centre in north east Victoria. Growth in Wangaratta is also strong. |

What is changing?

The world and our region are changing rapidly and north east Victoria is more interconnected across multiple spatial scales than ever before. The table below describes some of the major drivers of change and what this means for the Urban and Peri Urban landscape.

Drivers of change

| Driver of change | Leading to |

| Rapid population growth and urbanisation | Wodonga is one of Victoria’s top five fastest growing regional cities. Structural dwellings in Wodonga are forecast to increase by between 36.6% between 2016 and 2036 and 14.9% in Wangaratta, creating pressure on surrounding agricultural land and natural areas.[50] Development of vacant industrial zoned land in Wangaratta is likely to continue to increase, with 190 ha notionally available for development.[51] Urbanisation and urban growth are increasing the number of impervious surfaces, changing runoff regimes and impacting on water quality through increased contribution of nutrients and pollutants. Increased urban and peri urban development is encroaching into riparian and floodplain areas. Water sensitive urban design is now being advocated for, and included, in growth area planning. Proposal for a large scale (62 ha) solar power facility in North Wangaratta. |

| Climate change and acute shocks and extreme events | Increased extreme heat events, with more frequent days over 38oC leading to heat stress impacts within urban and other areas. Goulburn-Murray Water has forecast a reduction in water reliability for Wangaratta caused by changes in inflows under new climate change conditions.[52] Increased frequency of extreme events including storms, floods, droughts and blue green algae and even fire increasingly threatening peri urban areas. Increased fear of falling trees and vegetation causing fire risk, leading to increased clearing of native vegetation and other habitat. Both cities and peri urban landscapes were drought-affected between 2018-20. Wangaratta was particularly vulnerable with low water availability. Over the past 30 years (1989-2018) temperatures above 44oC have been recorded for Wodonga four times. Before this, the last time Wodonga exceeded 44oC was 1968. Instances of consecutive days above 38oC have also been more frequent in the past 30 years.[53] Declining average rainfall and reduced stream flow in waterways. |

| Change in governance | Empowerment and self-determination of Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples is being integrated into planning and community decision making. Recognition of Traditional Owners as Registered Aboriginal Parties (RAPs) is often contested between multiple Traditional Owners/First Nations groups. Increased interest in learning about Traditional Owners’/First Nations Peoples’ history and culture and integration of cultural objectives and methods into NRM. Increased standards of community engagement by government agencies, increasing local input into natural resource management planning and decision making. |

| Increase in visitation and recreational use of natural areas | Increased impact on natural environments through increased visitation with impacts including physical degradation, littering, noise and trampling vegetation. Increased connection and stewardship of natural areas by local communities. Potential increases in public access to Crown land water frontages with grazing licences. Increase in the diversity of values and how people engage with nature and expectations for services. |

Outcomes and priority directions

Key outcomes and priority directions for the RCS have been developed, drawing on information and discussions with people who live, work, visit and connect with north east Victoria.

Outcomes and their associated priority directions, that are important to the Urban and Peri Urban landscape from the regional themes of biodiversity, water, land and community include:

Biodiversity

- By 2040, increased extent (ha) and connectivity of native vegetation across north east Victoria.

- By 2040, an increase in the area of protected natural environments and enhanced remnant vegetation.

- By 2040, improved trajectories for priority native icon, threatened and culturally significant species and ecological communities (priority species and communities).

- By 2040, an increase in understanding and focus on supporting resilient biodiversity in a changing climate.

Land

- By 2040, land management practices are culturally appropriate reflecting Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples aspirations.

- By 2040, community resilience and land management practices are continually adapting to accommodate challenges of climate change and extreme events.

Community

- By 2040, an increase in the number and diversity of individuals and organisations supporting Landcare and Community NRM groups in north east Victoria.

- By 2040, an increase in participation by visitors and absentee landholders caring for, and stewarding the natural environment across north east Victoria.

- By 2040, an increased diversity of investment in NRM in north east Victoria.

- By 2040, Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples’ knowledge and practice is healing, adapted to a contemporary context and applied to both heal and care for Country.

Water

- By 2040, regional growth will create more liveable, productive and water sensitive urban and rural areas.

- By 2040, north east Victoria’s communities and industries continue to adapt to a future with less water due to reduced inflows from climatic changes, allowing for water to maintain environmental, cultural and recreational values.

- By 2040, waterways are healthy and well managed thereby protecting waterway dependent iconic, culturally important and threatened (priority species) species.

- By 2040, improved protection of water quality and waterway/wetland/floodplain system values during and following extreme events.