Vision

Biodiversity in north east Victoria is protected, improved, and valued for its cultural, social, and environmental significance

Introduction

North east Victoria is remarkably diverse. The region has extensive areas of high biodiversity value that are home to many threatened species. The region is valued for its natural beauty and the many benefits that natural areas provide to the community.

Facts

- More than 1,135,006 ha of land managed for conservation purposes and public use.

- 91 properties on private land permanently protected for high-value biodiversity assets.

- Approximately 400,000 ha of National and State Parks, providing habitat for:

- 227 rare or threatened flora species, including 60 nationally threatened

- 102 rare or threatened fauna species, including five nationally threatened

- 11 threatened ecological communities

- Highly valued cultural species e.g. bogong moth (Agrotis infusa).

Features

Native vegetation

The region hosts large areas of relatively intact native vegetation that support ecosystem health, provide habitat for wildlife, and contribute to the ecosystem systems upon which all life depends.

There are at least 2,264 species of known plants in the region, of which 227 are considered threatened.

Significant native vegetation across the region includes:

- Alpine and sub-alpine environments that support a range of ecological communities, e.g. tall, wet, fern-filled forests; snow gum woodlands; alpine peatlands; and meadows of wildflowers in summer and autumn

- Scattered paddock trees that are highly valued by the community, adding to the amenity and connectivity across the region

- Floodplain areas hosting some of the healthiest river red gum forests in the Murray-Darling Basin and extensive areas of connected riparian vegetation along waterways

- Remnants of critically endangered grassy woodlands and derived grasslands that provide complex habitat structures critical for the survival of vulnerable species, such as woodland birds and the crimson spider orchid (Caledenia concolor)

- Extensive areas of forest on public land, including over 264,000 hectares of old-growth forest with some of the world’s biggest trees, such as mountain ash (Eucalyptus regnans) and the alpine ash (Eucalyptus delegatensis)

- Species that are not known to occur anywhere else but north east Victoria, such as the summer leek orchid (Prasophyllum uvidulum) at Pheasant Creek Flora Reserve and the enigmatic greenhood orchid (Pterostylis aenigma) near Omeo.

Native animals

The diverse landscapes of north east Victoria provide habitat for at least 520 known native animals. Threatened species are spread across all landscapes.

Native iconic, threatened, and culturally significant species include, but are not limited to, the mountain pygmy-possum (Burramys parvus), bogong moth (Agrotis infusa), alpine she-oak skink (Cyclodomorphus praealtus), alpine spiny cray (Euastacus crassus), emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae), broad-shelled river turtle (Chelodina expansa), boorolong frog (Litoria booroolongensis) and the Murray crayfish (Euastacus armatus).

Abundant and diverse birdlife is also an important feature for the region’s community and ecosystems. Remnant native vegetation provides habitat for the Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 (FFG) listed Victorian Temperate Woodland Bird Community, which includes the nationally threatened regent honeyeater (Anthochaera phrygia) and swift parrot (Lathamus discolor), and other key species such as the turquoise parrot (Neophema pulchella), grey-crowned babbler (Pomatostomus temporalis), diamond firetail (Stagonopleura guttata) and the painted honeyeater (Grantiella picta).

Important attributes

North east Victoria’s community and visitors interact with the region for many reasons and hold shared and varying values. These values are further described in the local landscape sections. The important attributes associated with biodiversity identified by those who work, live, visit and connect with the region are:

- Healthy and functioning ecosystems and diverse flora and fauna

- Large areas of parks and reserves managed for conservation and/or recreation

- Connected native vegetation, stands of old-growth forest and paddock trees

- Native iconic, threatened and culturally significant species and ecological communities

- Iconic landscapes, e.g. river red gum forests, grassy woodlands and alpine areas.

Snapshot of condition

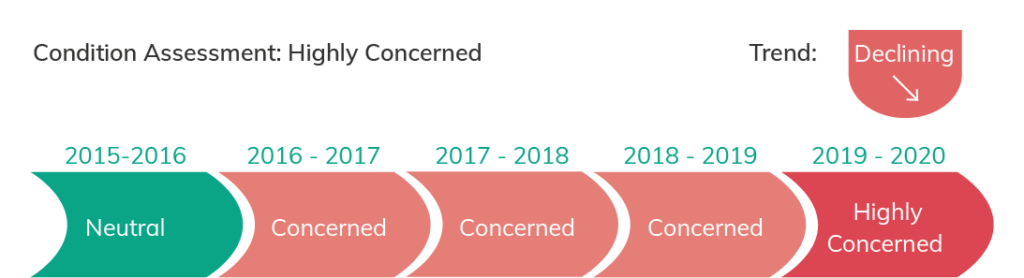

The section below provides a snapshot of the condition of biodiversity in north east Victoria.*

For the purpose of this RCS, the condition for the region’s biodiversity is considered to be highly concerning and in decline in 2019-20 when compared with previous years’ North East CMA’s catchment condition assessments.

The declining trend is predominantly due to historical pressures, such as introduced animal and plant species and land clearing being exacerbated by the increasing trends of urban encroachment, habitat fragmentation, climate variability and the spread of invasive species and diseases. The impacts of the recent bushfires also contribute to the highly concerned trend.

There is a relatively steady long-term incremental decline in biodiversity across much of the landscape. Symptoms include a decline in habitat quality, species threatened with extinction, and declining condition of some waterways.

The northern part of the region has been extensively altered since European settlement, with vegetation clearing associated with agriculture and development in the productive plains and valleys.

The condition assessment is informed by a range of indicators that are described further in this section. These include:

- Extent of native vegetation

- Area of permanent protection

- Connectivity

- Native priority species and ecological communities

- Threat control.

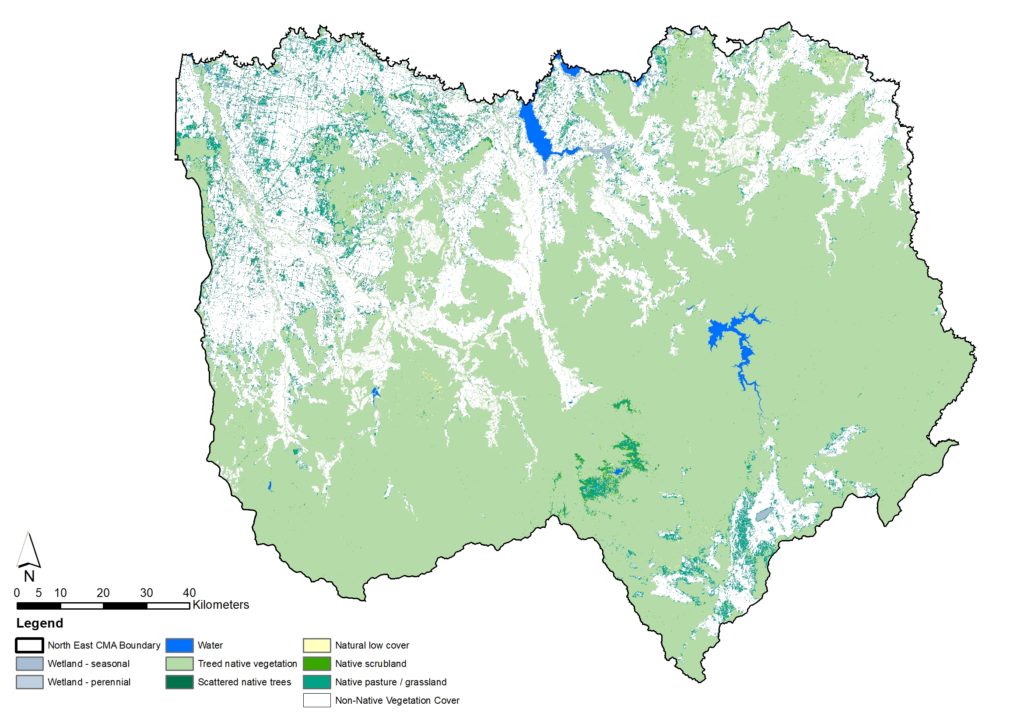

Extent of native vegetation

The extent and quality of native vegetation varies across the region, resulting from the legacy of over 200 years of clearing and altered management. While native vegetation has been largely retained in approximately 65% of the region (Figure 2), clearing for agriculture has been extensive in the more fertile valleys and plains.

Native grassy woodland communities are the most depleted, with only 2% of the plains woodlands remaining.

Since 1985, 93% of the region’s native vegetation has been minimally altered, thanks to the large parcels of native vegetation protected and managed under public land reserves.

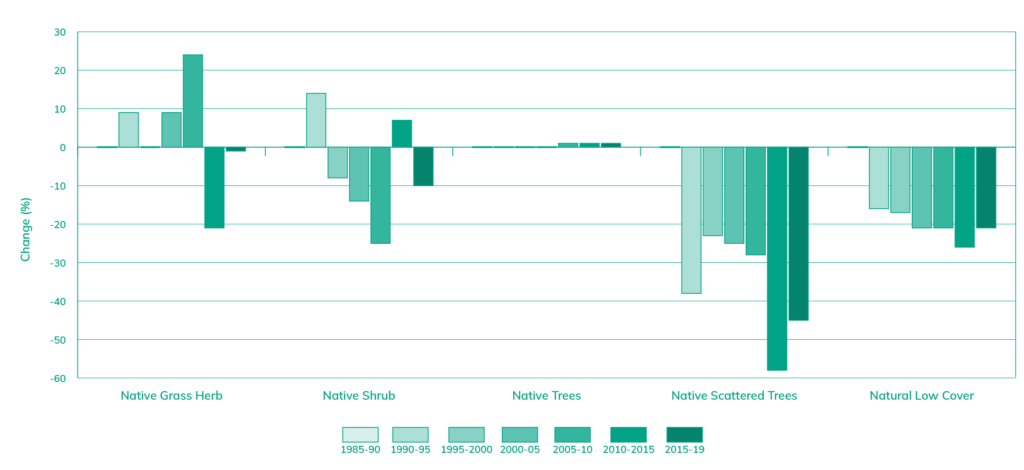

More than 11,000 ha of vegetation cover has been lost across north east Victoria since 1985 (Table 1), with some vegetation classes more significantly impacted than others.

| Native vegetation class | 1985-90 | 1990-95 | 1995-2000 | 2000-05 | 2005-10 | 2010-15 | 2015-19 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Native Grass Herb | 60,173 | 65,704 | 60,419 | 65,353 | 74,797 | 47,804 | 59,831 |

| Native Shrub | 8,732 | 9,967 | 8,009 | 7,470 | 6,510 | 9,330 | 7,820 |

| Native Trees | 1,251,395 | 1,259,212 | 1,258,935 | 1,260,023 | 1,261,433 | 1,264,801 | 1,265,273 |

| Native Scattered Trees | 50,668 | 31,300 | 39,239 | 38,005 | 36,599 | 21,053 | 27,770 |

| Natural Low Cover | 4,905 | 4,141 | 4,053 | 3,886 | 3,872 | 3,613 | 3,882 |

Native scattered trees, including paddock trees, have experienced a significant decline of 45% of cover in past decades compared to the 1985-90 baseline data (Figure 3).

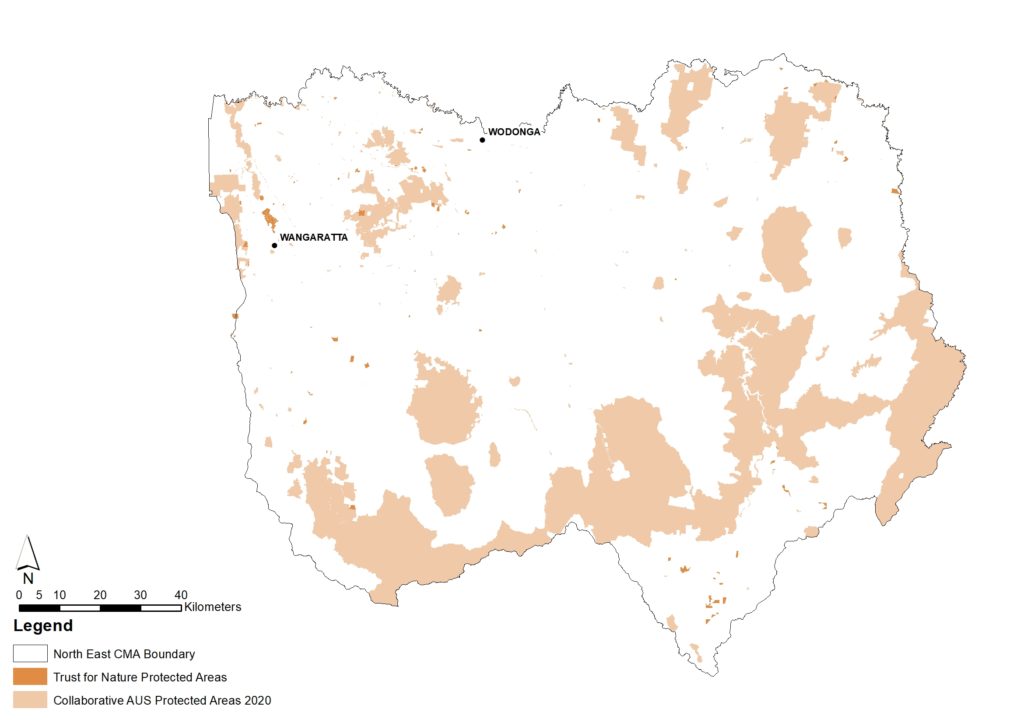

Area of permanent protection

Public land compromises 55% of north east Victoria, which includes large areas of permanent protection as part of a National Park, State Park or other public lands (570,622 ha). Additionally, over 5,000 ha of private land is protected by conservation covenants and private reserves (Table 2), with 300 ha established in the past five years.

| Protection type | Number of protected areas | Total area (ha) | Proportion of total protected areas in the region (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| National Park | 6 | 376,672 | 65% |

| State Park | 3 | 19,521 | 3% |

| Others (Public land) * | 249 | 174,429 | 30% |

| Conservation Covenants | 92 | 4,986 | 1% |

| Others (Private land) ** | 2 | 188 | < 1% |

| Total | 352 | 575,798 | 100% |

*Others (Public land): Historical and Cultural Features Area, Natural Features Reserve, Nature Conservation Reserve, Regional Park, Scenic Reserve, State Forest, Wilderness Areas.

**Others (Private land): Private Nature Reserve.

Connectivity

Structural connectivity between landscapes influences species distribution, movement and gene flow.

A range of features across north east Victoria provide connectivity, including extensive tracts of public land, roadside reserves, riparian vegetation and vegetation remnants on private land.

Native priority species and ecological communities

There are different approaches to identifying priority species and ecological communities for protection and enhancement. Priority native species and ecological communities can be:

- Culturally significant to Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples

- Iconic and important to the general community for social, cultural or economic reasons

- Threatened as defined by the commonwealth’s EPBC Act 1999, Victoria’s FFG Act 1988 and FFG Act Threatened List.

North east Victoria has a high number of threatened species and communities listed under the EPBC Act 1999 and/or the FFG Threatened List, including:

- 227 rare or threatened flora species, including 60 nationally threatened

- 102 rare or threatened fauna species, including five nationally threatened

- 11 threatened ecological communities.

Of the flora and fauna species in the region:

- 20 species are declared as endangered

- 32 species are declared as vulnerable

- One species is declared as conservation dependent.

All Country and species are culturally significant to Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples, but species of particular note in the region include the emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae), broad shelled turtle (Chelodina expansa), bogong moth (Agrotis infusa) and the mountain pygmy-possum (Burramys parvus).

There are also many iconic native species and ecological communities in the region, such as the brolga (Grus rubicunda), regent honeyeater (Xanthomyza Phrygia), Murray cod (Maccullochella peelii), Macquarie perch (Macquaria australasica), platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus) and alpine peatlands.

Condition of priority native species and ecological communities

Click on the icons to find a snapshot of the condition of some priority species and communities across north east Victoria.

Threat control

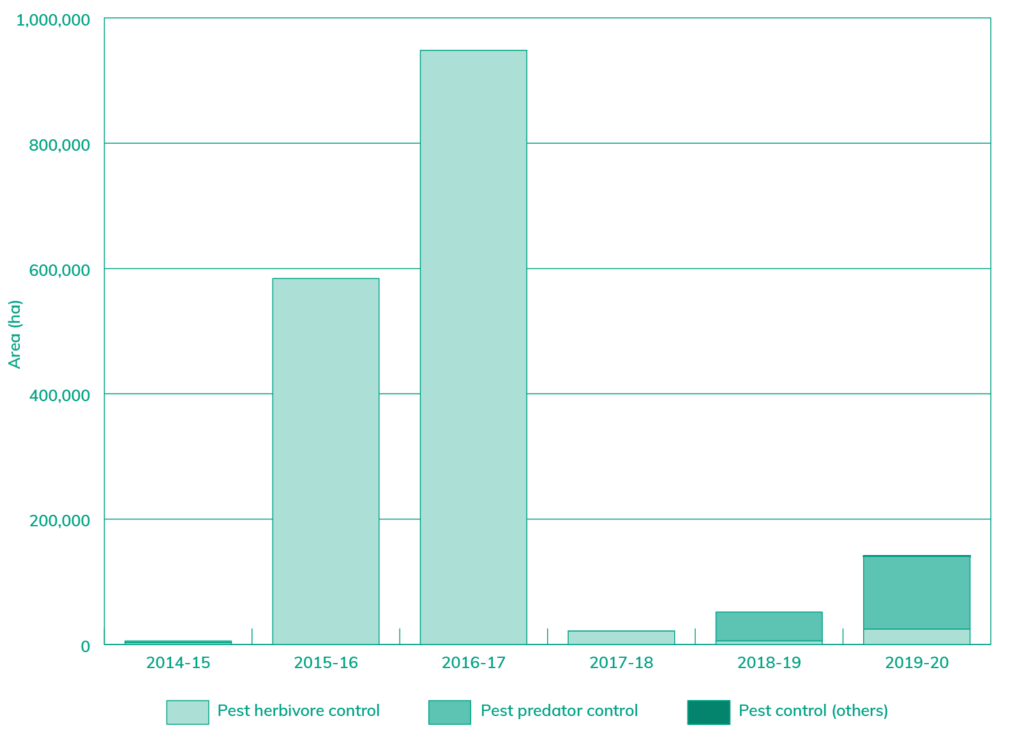

Invasive pest animals and weeds are among the main threats to biodiversity, impacting environmental and socio-economic systems. Displacing and competing with native species and altering habitat, the spread of pest animals and weeds contributes to the ongoing decline of the biodiversity condition in the region.

The following section provides a snapshot of threat control linked to North East CMA initiatives to provide a baseline of data for future comparison. There are many more hectares of threat control undertaken by the community and other private and public land managers across north east Victoria.

Pest control

Invasive pest animals are one of the main threats to biodiversity, impacting environmental and socio-economic systems.

There are increasing populations of invasive animals such as european carp (Cyprinus carpio), deer (Cervus spp. and Axis spp.), cats (Felis catus) and feral horses (Equus caballus) across north east Victoria.

In 2019-20, North East CMA initiatives resulted in 135,736 ha of pest predator and herbivore control (Figure 5).

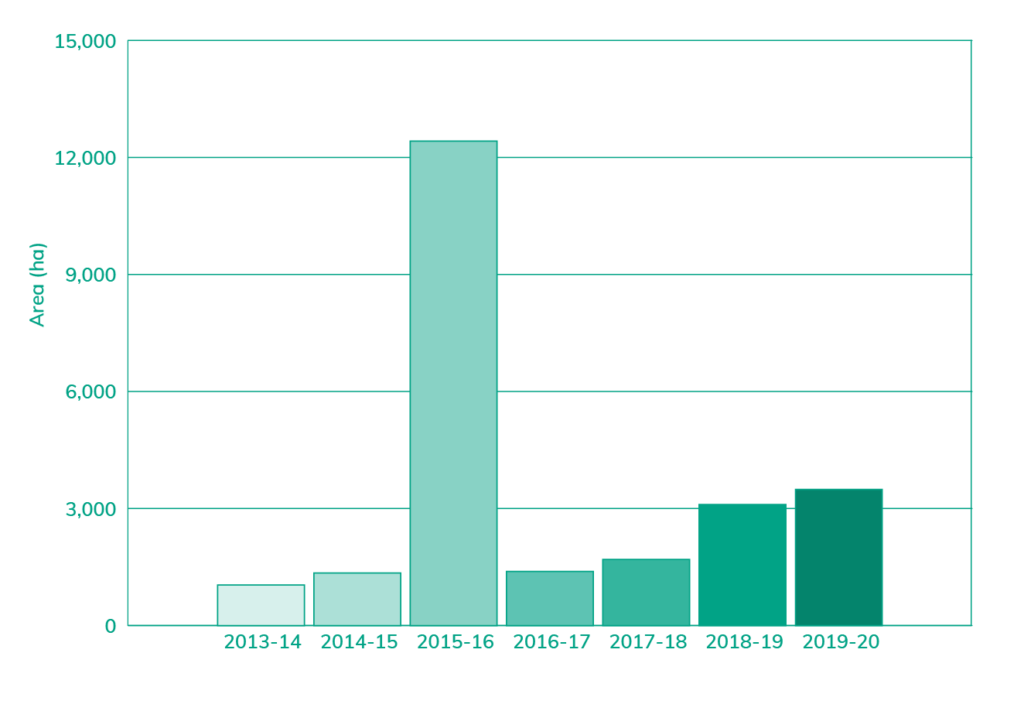

Weed control

Environmental weeds significantly impact the quality of remnant native vegetation and habitat for fauna. Weeds also decrease agricultural land productivity, impact recreational opportunities, and pose challenges to the management of pest animals that benefit from the shelter provided by them.

The increased spread of weeds across the landscape in the past decade is a rising concern among the community and land managers in the region.

In 2019-20, North East CMA initiatives resulted in 1,206 ha of weed control across north East Victoria (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Area of North East CMA supported weed control initiatives in north east Victoria between 2013 and 2020.

*Please note, the snapshot of condition section does not incorporate assessments of Healthy Country by Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples. Throughout the RCS renewal and implementation, we are committed to working with Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples to restore and protect Traditional Owner/First Nations Peoples knowledge systems and to integrate Healthy Country Assessments into monitoring and evaluation processes; acknowledging that traditional ecological knowledge and indigenous knowledge and practice will be protected under the authority of each Traditional Owner/First nations custodian and group.

What is changing?

The world and our region are changing rapidly and our region is more interconnected across multiple spatial scales than ever before.

The fundamental drivers of change described in the Our Region – What is changing? section influence all systems and landscapes in north east Victoria.

The table below provides additional changes and specific insights into what this means for the region’s biodiversity.

| Driver of change | Leading to |

| Climate change | Change in the range of aquatic and terrestrial plants and animals. Increased heat stress for flora and fauna. Increase in the spread of diseases (e.g. chytrid fungus). Increased frequency and intensity of bushfires impacting on long-lived species and may lead to significant long-term changes to some vegetation communities, e.g. alpine ash forests. Decrease in the resilience of native flora and fauna. A south-easterly shift in suitable climates that will push species towards the alps and into higher elevations, which may become a climate refuge. Refuge for species that rely on the cool upland habitat will be limited. Temperature shifts or changes in seasonal systems may be catastrophic for some species. Most vulnerable ecosystems include alpine regions and fragmented landscapes, where species have restricted niches or are not able to migrate. |

| Increase in tourism and visitor numbers | Increased nature-based tourism and recreation and intensified use of parks and reserves that are reaching carrying capacity. Impacts of physical degradation, littering, noise, trampling vegetation, introduction and spread of weeds, and disease (e.g. myrtle rust and cinnamon fungus). Vegetation clearing for the creation and/or expansion of camping sites and associated amenities (e.g. parking lots, bathrooms). Opportunities to engage with a new visitors in the protection and enhancement of natural areas. Increase in the diversity of values and how people engage with nature. |

| Change in land use and urban growth | Increase in urbanisation and urban growth and associated loss and fragmentation of habitat, run-off, and pollution impacting wildlife. Further fragmentation and loss of paddock trees as the urban and semi-urban boundaries expand into agricultural lands and mixed grazing is converted to dryland cropping – decreasing connectivity for species movement. |

| Acute shocks | Major bushfires directly affecting native species survival, reducing habitat quality and availability and intensifying the impacts of other threats, such as pest animals and weeds. |

| Increasing role and recognition of Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples | Increase in joint and co-management of Parks and reserves between Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples and government agencies. Increase in Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples involvement in delivering programs and on-ground works. |

| Increase in pest plants and animals | Increase in numbers and changes in distribution and range of pest plants and animals. Decrease in quality of habitat for native flora and flora. Increase in competition for food and resources between invasive and native species. Local biodiversity declines as the spread of invasive species reduces native diversity. |

Resilience insights

The changes described above directly impact biodiversity in north east Victoria.

To build resilience, we need to understand if these changes are strengthening or reducing the resilience of biodiversity and thresholds. Thresholds are known limits for characteristics of biodiversity that, if reached, trigger a change in biodiversity and its critical attributes.

Often thresholds are based on western science and quantitative data. Thresholds in this strategy include consideration of available science, data, traditional ecological knowledge and community knowledge.

In many cases, there is insufficient knowledge or data to determine thresholds. We will continue to work to build understanding and knowledge of thresholds during the life of the RCS. Consideration of these thresholds will be considered in the development of the detailed monitoring and evaluation plan for the strategy.

| Factors strengthening resilience | Factors reducing resilience | Thresholds |

|---|---|---|

| Threat reduction, e.g. pest animal and plant species control and management. Diversity of indigenous species of flora and fauna and ecological communities across north east Victoria. Diversity of habitats. Protection of large areas of remnant native vegetation. Protection of isolated and fragmented patches of remnant native vegetation. Extent and connectivity of protected land providing refugia for species from climate change and allowing species migration and movement. | Climate variability, with extreme weather events becoming more frequent and intense, resulting in less time to recover, e.g. bushfires and longer dry seasons. Removal of native vegetation, including old and ancient trees. Habitat loss and fragmentation, decreasing landscape connectivity. Spread of invasive pest species and environmental weeds. Changes in governance structures that slow down responses. | Vegetation cover > 50% to reduce wind erosion and > 70% to up 100% to reduce water erosion. Environmental offsets gaps – young trees do not provide the same cultural and ecosystem values as older trees. Maintain the minimum fire interval for the viability of fauna and flora species. E.g. > 20 years fire interval for successful regeneration of alpine ash. No native vegetation cover loss > 30%. No disconnection gap > 50 m between vegetation patches. |

| Strong partnerships and commitment to targets across NRM organisations, industry and the community, e.g. Regional Land Partnerships, Biodiversity 2037. Large number and range of volunteers, Landcare and community groups undertaking on-ground projects and activities to improve habitat and biodiversity. Sustainable land management practices on private land. Programs supporting private land managers to protect remnant native vegetation. Nature-based tourism that is valued by the community and attracts visitors and investment to protect natural environments. Landholders and managers practicing catchment stewardship and considering integrated catchment management. Traditional Owner/First Nations Peoples healing knowledge and country and increasingly involved in managing and governing country. | Unsustainable land use change and management practices. Land use changes, such as urbanisation encroaching on rural areas, resulting in vegetation loss. Soil degradation. Damage to critical habitat from visitor disturbance. | Visitor numbers within Parks and Reserves carrying capacity. Less than 25% weed cover in vegetation remnants. |

Outcomes and priority directions

Vision (By 2050)

Biodiversity in the north east Victoria is protected, improved, and valued for its cultural, social, and environmental significance.

The table below describes the course we will take to move towards our vision for biodiversity by providing:

Long-term outcome – these describe where we want to be in 20 years

Medium-term outcomes – these describe what we are currently doing and where we want to be in six years and help us to measure success in moving towards our vision and long-term outcomes

Established priority directions – what we are currently doing and want to continue to do over the next six years. They will help us build resilience in the face of change. Many of these directions are about persisting and adapting to change.

Pathway priority directions – ways forward over the next six years, that are not currently common practice in the region. They will help us adapt to change and are bridging activities between the current way of doing things to moving to a fundamental change.

Transforming priority directions – new practices that create a new way of doing things, that will be investigated, and where feasible implemented over the next six years or outside the lifetime of this RCS.

We will implement all three strategic directions, existing, pathway and transforming, to achieve our vision.

It is also recognised there is a need for a shift in current approaches to planning and management paradigms, so that Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples can heal Country and culture, through application of cultural knowledge and practice. This will take time. Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples will guide the process using Traditional Owners Strategic Framework for Managing Country outlined in the Victorian Traditional Owners Cultural Landscapes Strategy.

1. By 2040, the extent (ha) and connectivity of native vegetation across north east Victoria is increased

| Medium-term outcomes | Established priority directions | Pathway priority directions | Transforming priority directions |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 By 2027, the extent of native trees and native scattered trees has increased from 2015-19 levels (1,273,093 ha). 1.2 By 2027, there is an increase in the extent of native grasses and herbs from 2015-19 levels (59,831 ha). 1.3 By 2027, there is increased connectivity between native vegetation patches through revegetation in priority locations* supporting the movement of woodland birds. | 1.4 Revegetation to increase connectivity, patch size, shade and shelter and to protect riparian areas through community initiatives and formal incentives. 1.5 Promoting urban habitat creation. 1.6 Enforcing native vegetation clearance regulations. 1.7 Promoting the role of biodiversity and native vegetation on private land. 1.8 Supporting land managers to incorporate conservation actions into land management. 1.9 Investigating carbon trading activities that could provide biodiversity co-benefits across the landscape. | 1.10 Identifying priority locations for native vegetation connectivity and carbon/vegetation offset opportunities. 1.11 All revegetation for connectivity is biodiverse and climate ready. 1.12 Establishing biodiverse firewood plantations to reduce the impact of firewood collection and increase connectivity across the landscape. 1.13 Increased resources, support and legal advice for local government to enforce native vegetation clearance. 1.14 Traditional practices such as cool season burning embedded into policy and management to improve biodiversity. 1.15 Promoting carbon trading opportunities to land managers that could provide biodiversity co-benefits across the landscape. 1.16 Supporting landholders to protect and enhance farm dam vegetation. | 1.17 Purchasing vegetation for carbon offsets. 1.18 Establishing large-scale revegetation sites that create habitat connectivity across the region. 1.19 Large-scale revegetation for carbon sequestration partnerships established with biodiversity co-benefits. 1.20 16,000 hectares of revegetation in priority locations for habitat connectivity by 2027 in north east Victoria |

2. By 2040, there is an increased area of natural environments protected and remnant vegetation is enhanced

| Medium-term outcomes | Established priority directions | Pathway priority directions | Transforming priority directions |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2.1 By 2027, an increase in the extent of (ha) of private land protected by conservation covenants. 2.2 By 2027, an increase in the extent (ha) of private land managed to steward biodiversity. 2.3 By 2027, an increase in the extent (ha) of existing and remnant native vegetation enhanced to improve condition. | 2.4 Private land protected and managed through conservation covenants to protect biodiversity. 2.5 Land management agreements and incentives to improve and steward biodiversity on private and public land. 2.6 Providing landholders with support to plan and implement management of protected natural environments on private land. 2.7 Existing and remnant native vegetation is enhanced to improve quality. | 2.8 Additional stewardship partnerships between government, landholders and Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples investigated and trialed for the active management of biodiversity e.g. rate rebates, annual management payments, co-management arrangements. 2.9 Improved understanding of tipping points for priority species. | 2.10 Achievement of the Biodiversity 2037 targets of 17,000 ha of permanently protected private land by 2027 in north east Victoria. 2.11 Corporate and philanthropic partnerships established to purchase or steward land with ecological and connectivity values. 2.12 Sustainable land management covenants to protect biodiversity and manage other values e.g. agriculture, rural, lifestyle and amenity. |

3. By 2040, priority native icon, threatened and culturally significant species and ecological communities (priority species and communities) trajectories are improved

| Medium-term outcomes | Established priority directions | Pathway priority directions | Transforming priority directions |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3.1 By 2025, appropriate amendments are made in local planning schemes to include provisions and targets for protection of priority species and communities. 3.2 By 2027, an increase in the area of pest predator control (ha) in priority locations* with priority species and communities. 3.3 By 2027, an increase in the area of pest herbivore control (ha) in priority locations* with priority species and communities. 3.4 By 2027, an increase in the area of weed control (ha) with follow up treatment in priority locations* with priority species and communities. 3.5 By 2027, there is an increase in the development and application of Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples culturally significant species management plans. | 3.6 Maintenance protection and enhancement of priority locations for priority species and communities. 3.7 Landscape scale and targeted actions to reduce threats to threatened species and ecological communities. 3.8 Community and government partnerships for the management of invasive plants and animals. 3.9 Traditional Owner/First Nations Peoples resourced and supported to reconnect with culturally significant species. 3.10 Community involvement in citizen science. 3.11 Improved knowledge, research and monitoring of priority species and communities. 3.12 Reintroductions and translocations of priority species. 3.13 Appropriate fire regimes implemented for the protection of species and communities. | 3.14 Sustained weed, herbivore and pest predator control in areas with priority species and communities. 3.15 Identification of gaps in knowledge of keystone and/or culturally significant species and plans developed and implemented for their active management. 3.16 Further understanding and implementation of management activities to reduce disease related threatening processes (e.g. Chytrid fungus). 3.17 Strategic citizen science campaigns supporting other monitoring and informing management of priority species and communities. 3.18 Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples led events to raise awareness and protect culturally significant species 3.19 Use of artificial habitat and new technologies to improve trajectories of priority species and communities. 3.20 Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples-led fire programs and land management practices to improve outcomes for culturally significant species. | 3.21 Achievement of the Biodiversity 2037 targets of 496,000 ha under sustained herbivore control by 2027 in priority locations* across north east Victoria. 3.22 160,000 ha in priority locations under sustained pest predator control across priority locations* in north east Victoria. 3.23 224,000 ha in priority locations under sustained weed control across priority locations* in north east Victoria. 3.24 Collaboration with Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples to integrate cultural practices into management of culturally significant species. 3.25 Application of new technology to measure decline and improvement of species and communities. |

4. By 2040, there is increased understanding and focus on supporting resilient biodiversity in a changing climate

| Medium-term outcomes | Established priority directions | Pathway priority directions | Transforming priority directions |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4.1 By 2027, there is increased investment in programs that focus on improving biodiversity resilience in a changing climate. | 4.2 Biodiversity bushfire recovery investment following significant 2019-20 bushfires e.g. • predator & herbivore control • rescue, translocation, breeding and captive release • habitat restoration, riparian revegetation and waterway erosion management • weed control • alpine ash seed collection and reseeding. 4.3 Planning for protection of priority species and communities during active bushfires. 4.4 Research into the impact of climate change on priority species and communities. 4.5 Restoration of waterways with fencing, revegetation and erosion control to reduce sediment inputs during high flow events. 4.6 A fire management program which aims to maintain or improve the resilience of species and communities. | 4.7 Revegetation guides updated to suit a changing climate. 4.8 Incorporation of cultural practices and ceremony into biodiversity management. 4.9 Biodiverse urban greenspace planting and rural shade and shelter for a changing climate. 4.10 Research undertaken to better understand the impact of climate change on priority species and communities and implications for trajectory and management. 4.11 Local sustainable seed banks established that ensure the availability of seedlings for at-risk fire species and for climate-ready planting. 4.12 Support for landholders to protect and enhance farm dams to protect biodiversity in times of reduced water availability. 4.13 Trial and demonstration sites to test transformational opportunities to improve biodiversity resilience during a changing climate. 4.14 Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples resourced to support the recovery of culturally significant species following extreme events. | 4.15 Improve the common understanding and communication of what healthy country is for Traditional Owners/First nations Peoples. 4.16 Permanent and other protection providing refugia for priority species in a changing climate. 4.17 Species protection and management decisions are informed by climate risks, megatrends, traditional knowledge and contemporary science. |

*Priority locations will be informed by cost-benefit analysis from DELWP’s Strategic Management Prospects tool. Priority locations are the top ranked locations across Victoria. As at December 2022, these were generally the top 20% using SMPv3, where management actions maximise benefits to threatened (and other) species.