Vision

A diverse and connected community caring for and stewarding North East Victoria’s landscapes

Introduction

North east Victoria hosts a diversity of people, industries and landscapes, all of which contribute to what we know and love about the region.

There is a rich history of Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples managing and caring for Country which continues today.

There is a strong community commitment to improving the condition of natural resources across the region as evidenced by the active volunteering community and the uptake of partnership projects between government and community.

Facts

- Resident population 108,000 and growing.[25]

- 4.2 million daytrip and overnight visitors in 2019.[26]

- North east Victoria contributes approximately $5.55 billion in gross regional product which is around 6.2% of regional Victoria’s total.[27]

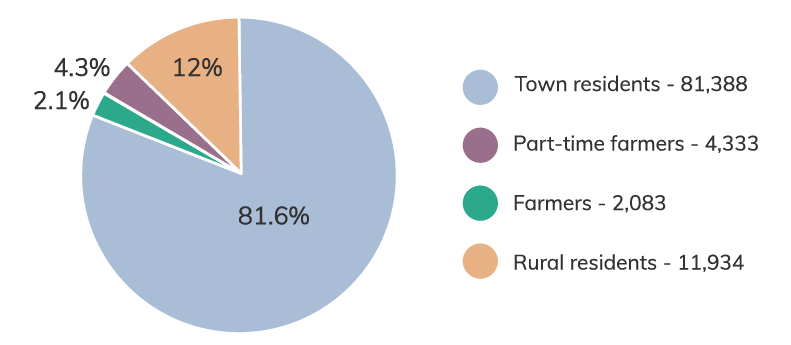

- 82% population urban residents.[28]

- 2% population full-time farmers.[29]

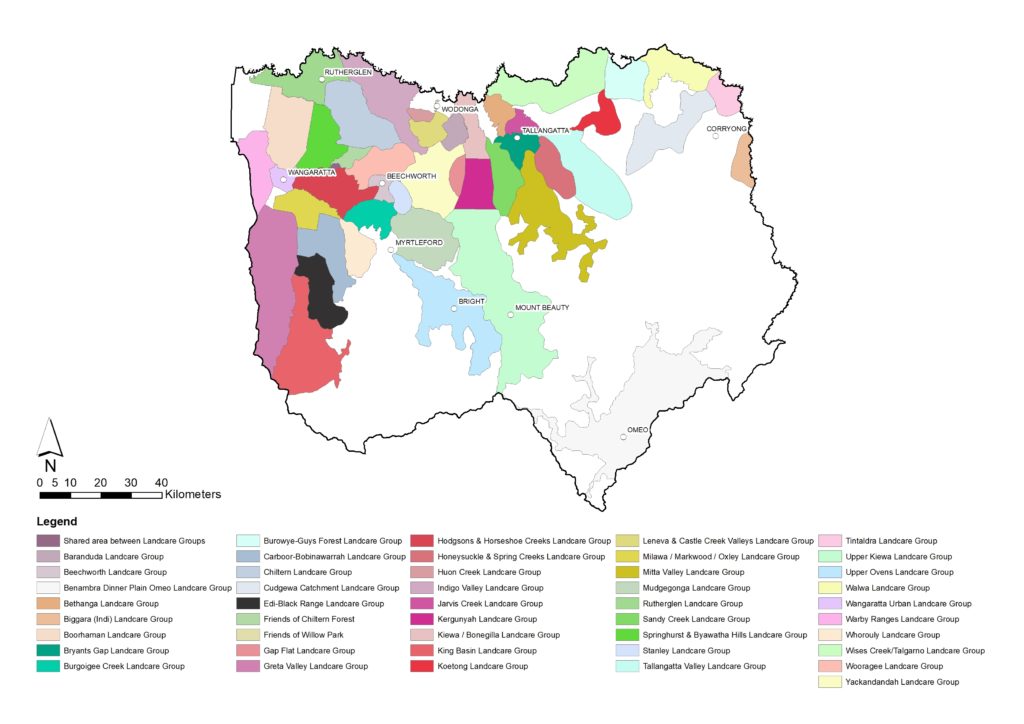

- Active volunteering community, including 54 registered Landcare groups, community NRM groups or networks.

- Two major regional centres – Wodonga and Wangaratta.

- Many smaller regional towns and villages scattered across the landscape.

- Health is the main employment industry. Hospitality, retail, education, public services and manufacturing are also important.

Features

Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples

For many thousands of years, local Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples have managed and cared for the Country across north east Victoria. In 1824 the Hume and Hovell expedition crossed the Ovens River at Whorouly, leading to the regional devastation of one of the oldest cultures in the world and the attempted removal of Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples from the land.

Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples physical presence in the region was reduced due to settlement, but connection to culture and Country has remained despite this, and north east Victoria has many Traditional Owners and First Nations Peoples who connect and care for Country today.

Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples are seeking decision making authority over the management of traditional territories.

North east Victoria has three Registered Aboriginal Parties, these include:

- Gunaikurnai Land and Waters Corporation

- Taungurung Land and Waters Council

- Yorta Yorta Aboriginal Corporation.

A map of the Registered Aboriginal Parties in Victoria can be found here.

Many other Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples groups care for, and have connection to north east Victoria. There is an open approach to working with all Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples groups who assert interests and rights across north east Victoria, in the development and implementation of the RCS. Some other groups include:

- Dhudhuroa Waywurru Nations Aboriginal Corporation

- Duduroa Dhargal Aboriginal Corporation

- Dalka Warra Mittung Aboriginal Corporation

- Jaithmathang Traditional Ancestral Bloodline Original Owners (TABOO)

- Bangerang Aboriginal Corporation.

Population

Around 80% of the region’s population reside in the regional centres and towns, with less than 20% of the population living in rural areas.[30]

Farming households comprise a small proportion of the total catchment population, with rural residents greatly outnumbering the farmer population in north east Victoria.

According to the 2016 census between 1% to 4% of the region’s population is Indigenous.

The population is ageing with the percentage of people aged over 65 increasing over the past 30 years.

Employment and industry[31]

Health is the main employment industry in north east Victoria. Other industries such as hospitality and manufacturing also feature strongly in certain areas of the region.

For the agricultural industry, north east Victoria is mostly a beef producing region, with 54% of farms being beef producers, occupying 55% of the area of agricultural land. Dairy, sheep, horticulture and grains account for most of the remaining agricultural production in the region.

Parts of the region are also tourism hotspots; in 2019 tourism contributed to 22% of the region’s gross regional product, with 4.5m overnight and daytrip visitors.

Volunteer groups

An active network of 54 Landcare groups and associated NRM groups or networks provide major support to the management of natural resources in north east Victoria. Legacy institutions like Landcare are an important feature of the community and represent a strong base for NRM engagement.

Important attributes

North east Victoria’s communities and visitors are diverse and hold shared and varying values that are further described in each local landscape section. The important socio-economic attributes identified by those who work, live, visit and connect with north east Victoria are:

- Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples, whose knowledge and practice has adapted to a contemporary context and applied to heal and care for Country

- Volunteerism and stewardship – active NRM and Landcare groups that self-organise, care for and contribute to the management of the region’s natural resources

- A strong sense of community connection, belonging and place

- Community resilience to extreme events and disasters

- Natural beauty, diversity of natural ecosystems, parks and resorts providing for social, cultural and recreational values for those who work, live, visit and connect with north east Victoria

- Healthy natural ecosystems, National, State and regional parks and alpine reserves and resorts.

Snapshot of condition

In line with the RCS vision for community, this section considers community condition in terms of their capacity and ability to care for, and steward north east Victoria’s landscapes and the connections that exist across communities to maintain resilience.

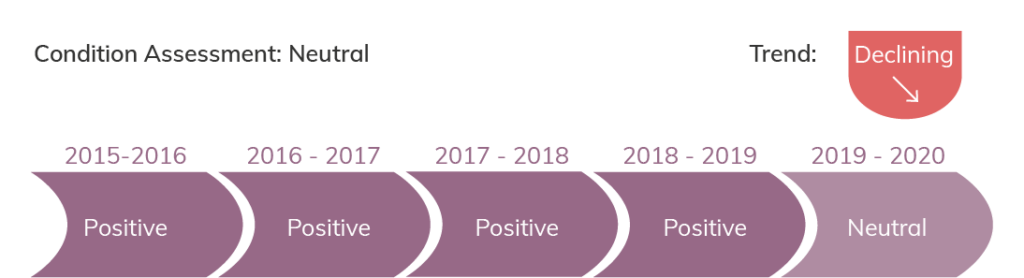

For the purpose of this strategy the condition within the community theme has been assessed as neutral in 2019-20, which is a decline from the positive condition in previous years’ North East CMA’s annual catchment condition reports. A series of shocks and events across the region since 2019 informs the current assessment of community condition as ‘declining’.

In 2019-20 fires affected 22% of north east Victoria and since 2000 more than one million hectares of the region’s land has been burnt twice. Apart from impacts on land, water, infrastructure and community resilience, fires have region-wide impacts on communities including concerns around fire risk and smoky conditions.

This increase in frequency and severity of fires and other extreme events such as droughts, floods and blue green algae events, directly impact communities and industries, economically and socially, and shortens community recovery windows.

In 2020, as in communities across the world, north east Victoria’s industries and communities were shocked by the impacts of coronavirus (COVID-19); challenging community connectivity, volunteering patterns, tourism, businesses and general community resilience.

The condition assessment is informed by a range of indicators that are described further in this section. These include:

- Population

- Visitation and absentee landholders

- Volunteering

- Stewardship

- Partnerships with Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples.

Population

In 2019 the Victorian Government report Victoria in Future provided projections for population growth in the region. This report estimated the population of north east Victoria is growing at a rate of between 3.2% and 31.9%[32] as shown in Table 1.

| Local Government area* | Population forecast | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 2021 | 2026 | 2031 | 2036 | % growth forecast 2016 to 2036 | |

| Alpine | 12,578 | 12,929 | 13,127 | 13,321 | 13,507 | 6.8% |

| Indigo | 16,165 | 16,884 | 17,428 | 17,977 | 18,515 | 12.6% |

| Towong | 6,046 | 6,102 | 6,151 | 6,199 | 6,246 | 3.2% |

| Wangaratta | 28,592 | 29,665 | 30,519 | 31,352 | 32,165 | 11.1% |

| Wodonga | 40,100 | 44,165 | 49,174 | 54,108 | 58,901 | 31.9% |

* Moira, East Gippsland and Mansfield data is not included, as most of the population is in other CMA areas.

Many parts of north east Victoria have experienced significantly higher population growth rates than what was projected in Victoria in Future. In the past 18 months to the middle of 2021, influenced by coronavirus (COVID-19), growth has further accelerated due to increased migration from capital cities to regional areas. As a result, in some regional centres, the growth projected for the next 15 years has been realised during the past two years.

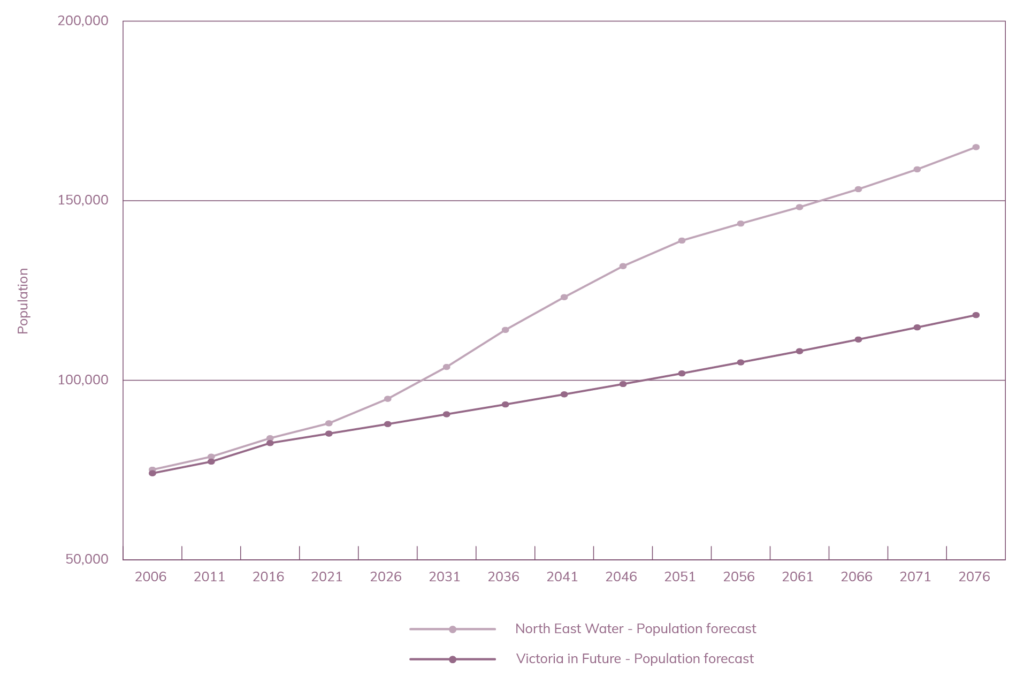

To plan for future infrastructure and community water needs, North East Water has developed new population projections for parts of the region serviced by mains water and sewer. These are based on ABS data, housing water connection data and discussions with local governments. These projections, shown in Figure 2 illustrate potentially higher levels of population growth for the region into the future.

North East Water acknowledges there is uncertainty in the projections, mainly whether the current rapid growth is a ‘step change’ that will eventually level out, or if the past 15 years’ growth rate is the ‘new normal’.

Information on how this is impacting dwelling growth within the region can be found in the Land theme snapshot of condition.

Visitation and absentee landholders

In 2019 the ‘High Country’ tourism sector delivered around 10% of domestic overnight visitors in regional Victoria.

Between 2014 and 2019 visitors, overnight stays and expenditure in north east Victoria steadily increased, with 34% additional visitors and 41% additional tourism related expenditure by 2019.

Due to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic and related reductions in domestic and international visitation, visitors to the region decreased by 54% and tourism expenditure by 61% in 2020.

| Visitation and expenditure 2014-2019[34] | Visitation and expenditure 2020[35] | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | % increase between 2014 – 2019 | 2020 | % decrease between 2019 – 2020 | |

| Visitors (000s) | 2,758 | 2,877 | 3,037 | 3,548 | 4,026 | 4,182 | 34% | 1,900 | 54% |

| Visitor nights (000s) | 4,532 | 4,322 | 4,836 | 5,528 | 6,286 | 6,052 | 25% | 3,000 | 50% |

| Expenditure ($m) | 746 | 709 | 824 | 1,050 | 1,233 | 1,269 | 41% | 490 | 61% |

Anecdotally during 2020-21, when Victoria’s coronavirus (COVID-19) restrictions allowed travel, visitor numbers across the region were higher than comparable periods in previous years. Anecdotal reports also suggest visitation to natural attractions such as National Parks had increased.

Figure 3 shows visitation to Mount Buffalo National Park, one of the region’s key natural attractions, over a 25-year period. This graph shows the impact of a number of changes in Park use and events, including the closure of downhill skiing, Mount Buffalo Chalet closure and fires. It also shows a steady increase in visitation between 2005 and 2019, the decrease in visitation during 2020 due to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic and the subsequent increase in 2020-21 when travel was again permitted.

According to the 2016 ABS census, 6,472 dwellings in the region were unoccupied or 14% of the total dwellings. With the census occurring mid-week this provides some indication of the level of weekender and accommodation dwellings within the region. Depending on the location this can also be an indication of dwelling vacancy in residential areas or dwelling abandonment in more remote areas.

Some towns across the region have high levels of accommodation and weekender dwellings shown by low occupancy levels in the census data. Bright and Mount Beauty recorded by far the highest levels of unoccupied dwellings on census night with 25%. Alpine resorts are also predominately accommodation-based dwellings.

Volunteering

General rates of volunteering are higher in regional Victoria than in metropolitan Melbourne. Towong has the highest rate of volunteering in north east Victoria, with 35-46% of people participating in volunteer activities, other local government areas all record between 26-34%, while Wodonga has the lowest level at between 17%-25%.

Across Australia rates of volunteering from culturally or linguistically diverse (CALD) communities is lower at 23%, compared to 32% for the remainder of the community.[36]

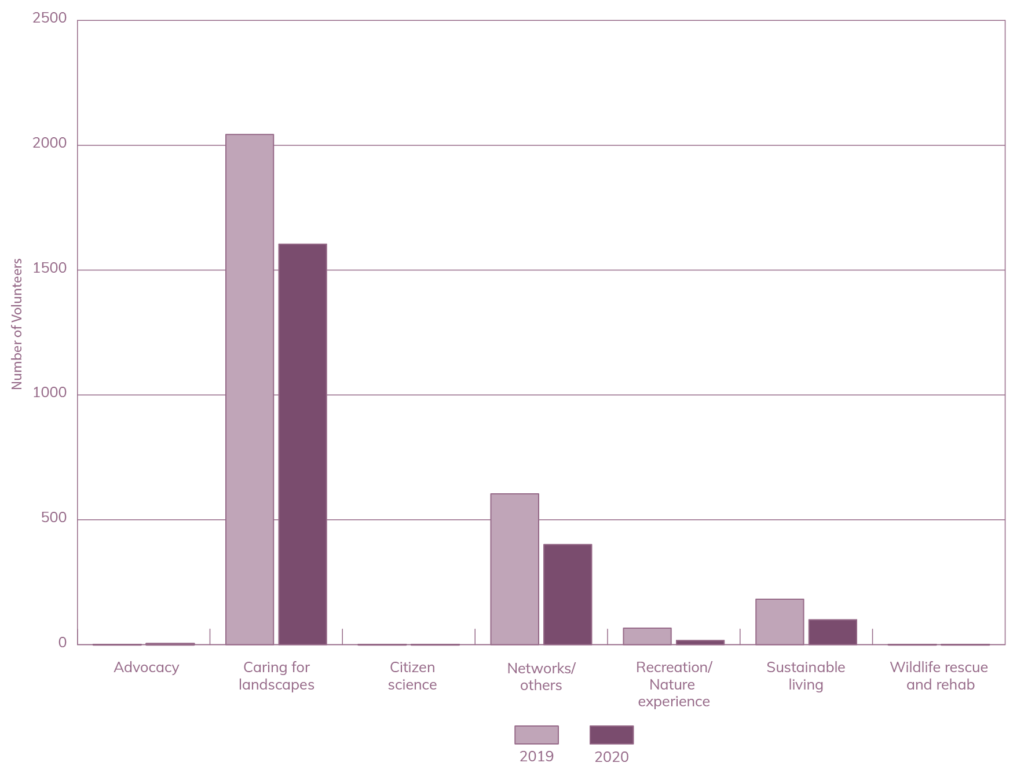

In 2019 more than 2,895 people volunteered in NRM and sustainability in north east Victoria (Figure 4), contributing nearly 60,000 hours, at a value of nearly $2.5 M to the community.

Rates of volunteering have been shown to be dropping across Australia, with a decrease from 42% of the population undertaking volunteering in 2006 to 32% in 2014.[37]

Recent studies have also shown that volunteers are increasingly seeking arrangements other than ongoing commitments. Short term project roles, events that occur once or infrequently, volunteering from home or virtually and volunteering of professional skills are some of the experiences that volunteers are seeking.[38]

Understandably lower levels of volunteer hours were seen in 2020, which is likely due to COVID-19 restrictions. Citizen science activities within the region are low.

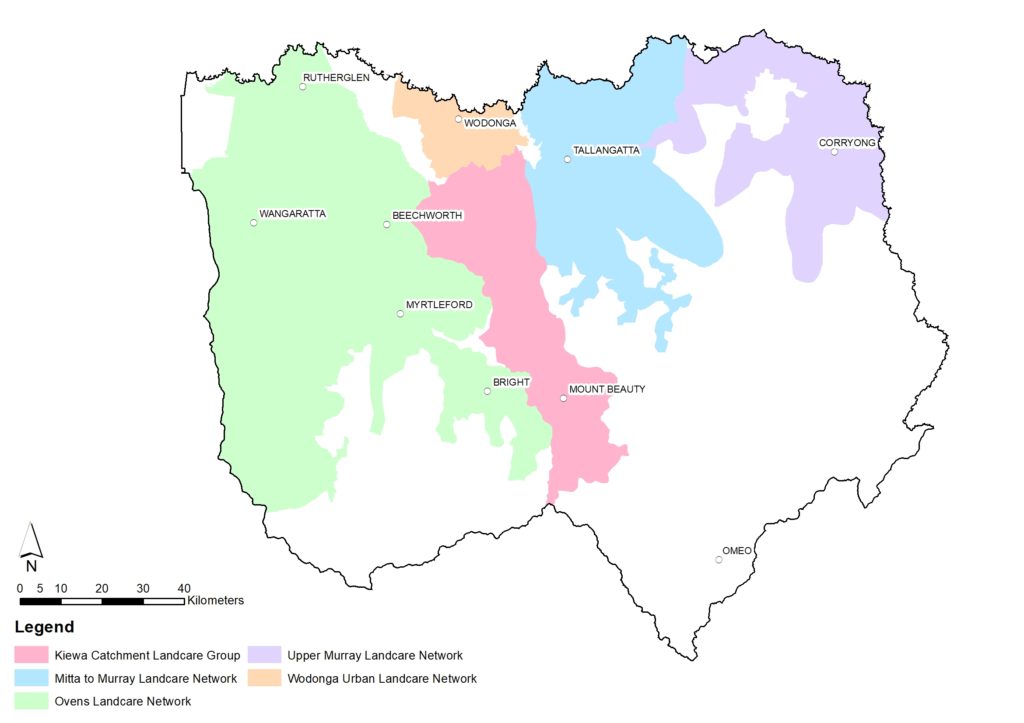

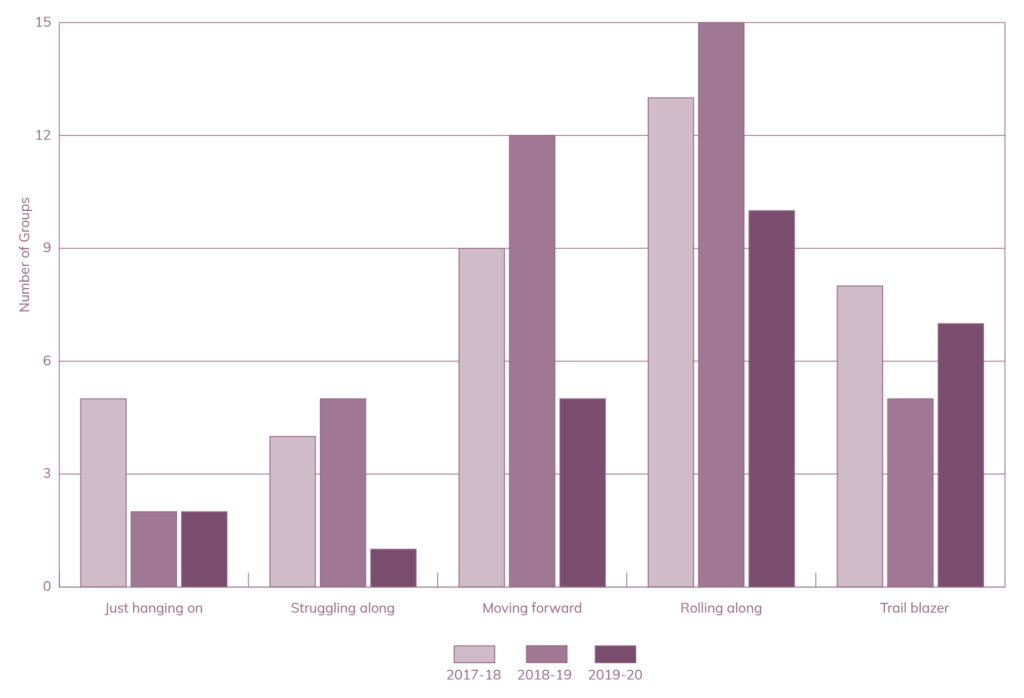

North east Victoria has an active network of 117 community groups supporting NRM and sustainability in the region, including 71 groups caring for landscapes, of which 54 are Landcare groups or associated NRM groups or networks.

Strong community cohesion and initiatives have given rise to new sustainability groups across north east Victoria, including Mitta to Murray Landcare Network, Wangaratta Sustainability Network, Totally Renewable Yackandandah, Beechworth Food Co-op, as well as more community gardens.

For the most part, Landcare groups in north east Victoria are operating in good health. Key challenges facing Landcare in the region include:

- The decline in NRM investment and the increasing competition for funding across more NRM and sustainability groups

- Access to recurring funding and funding for paid labour

- Attracting new and diverse volunteers into groups.

Stewardship

Communities caring for natural resources is more than just formal volunteering. Every day land managers are stewarding land with good land management practices and conservation initiatives. In addition to this:

- Across north east Victoria there are currently 92 private land managers who protect nearly 5,000 ha of land in perpeituity through conservation covenants, in partnership with Trust for Nature.

- Each year the North East CMA partners with more than 100 land managers to undertake stewardship work on the land they care for.

As demonstrated in Table 3, communities are also actively involved in contributing to planning and decision making, raising awareness and increasing their skills and capacity through attendance at events.

| Activity | No. participants 2018-19 | No. participants 2019-20 | Approximate hrs 2019-20 |

|---|---|---|---|

| North East CMA sponsored activities | |||

| Contributing to on-ground works | 36 landholder grants 94 management agreements issued | 83 landholder & NRM group grants 34 management agreements issued | 2,808 |

| Attending skills and training events | 3,916 | 2,621 | 399 |

| Awareness raising activities | 4,101 | 5,760 | 516 |

| Collaborating in planning and decision making | 3,791 | 3,368 | 539 |

| Other activities | |||

| Being consulted to determine appropriate action | 381 | 531 | 797 |

| Visiting parks | 3,100,000 | Data unavailable at time of report | Data unavailable at time of report |

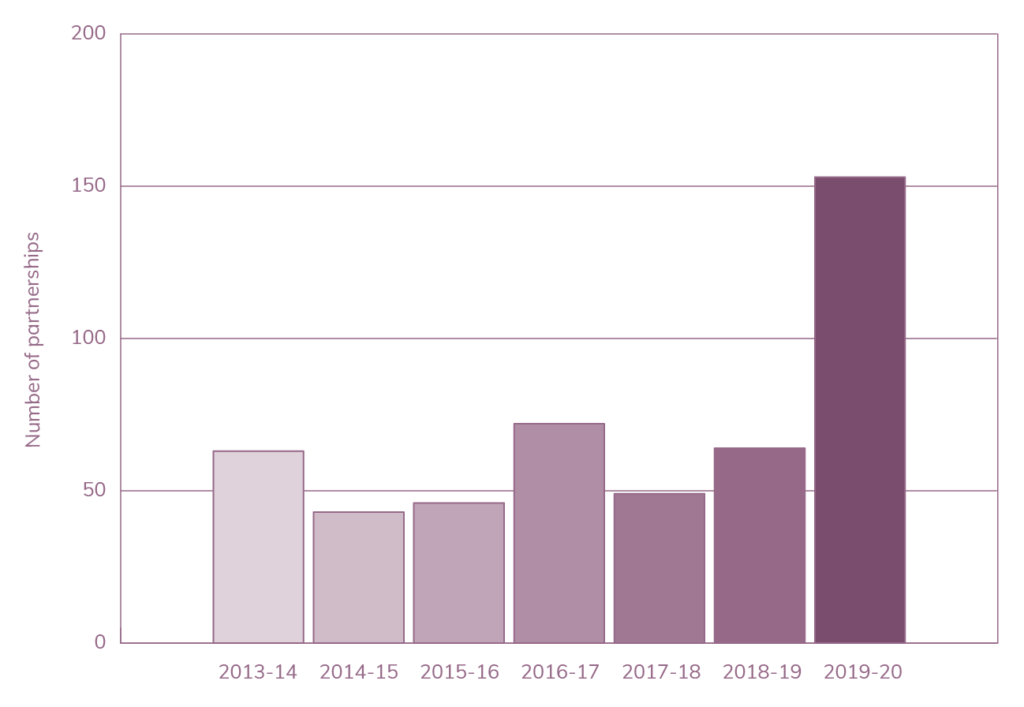

Total number of partnerships between the North East CMA, landholders and communities increased rapidly in 2019-20, which is likely attributed to Australian Government investment during this period.

Partnerships with Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples

There is a growing recognition of Traditional Owners’/First Nations Peoples’ self-determination, their rights and their role in NRM. There is also a growing commitment among Governments to elevate Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples’ role in the policy, planning and management of Country.

Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples take a holistic, adaptive approach to management of Country. Government, as a natural resource manager, has taken steps to bridge different planning, governance and management arrangements through joint and co-management of some areas of public land, developing partnerships with Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples and integrating Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples, cultural values, practices, objectives and knowledge (where permission has been granted) into NRM.

In 2021, Traditional Owners/First Nations groups have seven partnerships in place with North East CMA and four with Parks Victoria in north east Victoria. A partnership is defined as an association of two or more organisations/individuals that has been formalised in writing.

Throughout the implementation of the RCS, we are committed to continuing to work with Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples to enable the application of their knowledge and practices in NRM.

Please note, the snapshot of condition section does not incorporate assessments of Healthy Country by Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples. Throughout the RCS renewal and implementation, we are committed to working with Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples to restore and protect Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples knowledge systems and to integrate Healthy Country Assessments into monitoring and evaluation processes; acknowledging that traditional ecological knowledge and Indigenous knowledge and practice will be protected under the authority of each Traditional Owner/First Nations custodian and group.

What is changing?

The world and our region are changing rapidly and north east Victoria is more interconnected across multiple spatial scales than ever before.

The fundamental drivers of change described in the Our Region – What is changing? section influence all systems and landscapes in north east Victoria. These changes have been identified through socio-economic research and community/stakeholder engagement for the RCS renewal.[39]

Table 4 provides additional changes and specific insights into what this means for the community in north east Victoria.

| Driver of change | Leading to |

|---|---|

| Climate change | Climate change is a key concern for the community. Landholders and communities are increasingly seeking solutions and support to adapt to climate change and associated health impacts, such as extreme heat. Impacts on community health, wellbeing and social cohension during extreme events. Threatened viability of agriculture and snow-based industries. Significant threats to tangible and intangible cultural heritage. |

| Transition to service economy and growth | Increase in urban development, lifestyle holdings, and settlement sprawl, reducing available land for agricultural production and impacting farmers’ social license to operate. Decline in farming populations and numbers of landowners whose main occupation is farming, as other sectors of the economy provide more attractive career prospects for younger rural people. |

| Demographic transition | Changes in expectations for liveability, services, values and political representation. Wodonga is one of the five fastest-growing regional cities in Victoria, providing employment opportunities and the services demanded by working professionals. Indigo and Alpine local government areas have experienced significant growth in the past two years, likely associated with migration due to coronavirus (COVID-19). |

| Change in volunteering | Environmental awareness is growing as landholders and communities seek solutions and support to adapt to climate change and the health impacts associated with extreme heat. Change in the way communities engage in stewardship and volunteering with people seeking short-term and virtual volunteering options. Decrease in the number of volunteers. Members of volunteer groups are ageing. Increasing administrative burden and regulations on volunteer groups, which may also act as a barrier to recruiting new volunteers. |

| Increase in visitors and absentee landholders | Absentee landowners who are not always actively practising land stewardship. Opportunities to engage with new land managers and visitors to influence practices. Visitors who are not always aware of the stewardship responsibilities and practices that may cause harm to natural resources. |

| Acute shocks | Shocks such as the 2019-20 bushfires and the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic have impacted north east Victoria’s community resilience and volunteering in NRM. Impact of coronavirus (COVID-19) lockdowns and border closures on social interactions and the flow of goods and services into and out of the region. Online fatigue, as communities spend more time connected to the internet. |

| Increasing role and recognition of Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples | Increasing awareness of the rich Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples culture and community interest to learn more and enter partnerships to manage natural resources. Opportunities for two-way learning and collaboration between Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples and other land managers. Policy changes are increasing requirements for agencies to engage with Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples, with limited consideration of the impact on the time and costs required for genuine engagement. Acknowledgment that will take time (intergenerational timeframe) to accommodate healing and strengthening of Country. |

Resilience insights

The changes described above directly impact the community in the north east Victoria.

To build resilience of communities we need to understand if these changes are strengthening or reducing resilience and meeting thresholds. Thresholds are known limits for characteristics of the community that, if reached, trigger a change in communities and their important attributes.

Often thresholds are based on western science and quantitative data. Thresholds in this strategy include consideration of available science, data, traditional ecological knowledge and community knowledge.

In many cases, there is insufficient knowledge or data to determine thresholds. We will continue to work to build understanding and knowledge of thresholds during the life of the RCS. Consideration of these thresholds will be considered in the development of the detailed monitoring and evaluation plan for the strategy.

| Factors strengthening resilience | Factors reducing resilience | Thresholds |

|---|---|---|

| Self-determination and empowerment of Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples. Economic diversity and development. An active and involved community that cares and contributes to NRM and a diverse network of community, Landcare and NRM groups. Diversity of Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples. Retirees and professionals moving in and bringing their knowledge and experience. New community groups forming to tackle sustainability and NRM challenges. Land managers and communities are increasingly seeking solutions and support to address climate change risks, such as changes in commodities or management practices and the health impacts of extreme heat. Landholders and managers practicing catchment stewardship and considering integrated catchment management. Traditional Owner/First NationsPeoples healing knowledge and country and increasingly involved in managing and governing country. | Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples self-determination and empowerment is progressing but change in government approaches can be slow and intergenerational healing is required. Climate variability and extreme weather events are becoming more frequent and intense, resulting in less time for the community to recover. Movement of NRM knowledge out of the region with an ageing population and young people moving to the city. Absenteeism impacting on consistency of land management and conservation e.g. increase in weeds on some lifestyle properties. Limited access to recurrent funding and labour costs for community-led NRM activities. | Traditional Owners/First Nations groups recognised as Registered Aboriginal Parties by the Victorian Government across the whole of north east Victoria. NRM policy and procedure embed Traditional Owners’/First Nations’ Peoples knowledge and practices. Registered Aboriginal Parties and government jointly managing all National Parks in the region. NRM community groups leading initiatives to secure recurrent funding for NRM. NRM community groups continuing to increase participation. Visitors and absentee landholders involved in stewardship activities. |

Outcomes and priority directions

Vision (By 2050)

A diverse and connected community cares for and stewards north east Victoria’s landscapes

The table below describes the course we will take to move towards our vision for community by providing:

Long-term outcomes – these describe where we want to be in 20 years

Medium-term outcomes – these describe what we are currently doing and where we want to be in six years and help us to measure success in moving towards our vision and long-term outcomes

Established priority directions – what we are currently doing and want to continue to do over the next six years. They will help us build resilience in the face of change. Many of these directions are about persisting and adapting to change.

Pathway priority directions – ways forward over the next six years, that are not currently common practice in the region. They will help us adapt to change and are bridging activities between the current way of doing things to moving to a fundamental change.

Transforming priority directions – new practices that create a new way of doing things, that will be investigated, and where feasible implemented over the next six years or outside the lifetime of the RCS.

We will implement all three priority directions, Existing, Pathway and Transforming, to achieve our vision.

It is also recognised there is a need for a shift in current approaches to planning and management paradigms, so that Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples can heal Country and culture, through application of cultural knowledge and practice. This will take time. Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples will guide the process using the Traditional Owners Strategic Framework for Managing Country outlined in the Victorian Traditional Owners Cultural Landscapes Strategy.

1. By 2040, there is an increase in the number and diversity of individuals and organisations supporting NRM activities in north east Victoria.

| Medium-term outcomes | Established priority directions | Pathway priority directions | Transforming priority directions |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 By 2027, an increase in Landcare and community NRM group health. By 2027, there is an increase in the number of partnerships maintained or modified between CMAs and individuals/organisations and these are mutually beneficial across north east Victoria. 1.3 By 2027, an increased number of volunteers is involved in natural resource volunteering across north east Victoria. | 1.4 Existing volunteer groups supported to maintain momentum. 1.5 The contributions of natural resource volunteers is valued and recognised. 1.6 Adapt programs to engage more youth in NRM and volunteering. 1.7 Support and improve existing citizen science opportunities in the community. 1.8 Encourage young volunteers by engaging with schools and through links to school curriculum. 1.9 Support forums that encourage networking, collaboration and sharing between Landcare and community NRM groups. | 1.10 Volunteer groups supported to build capacity to attract an increased diversity of people to participate in natural resource volunteering. 1.11 Volunteer groups and initiatives adapting to attract greater diversity from all sectors of the community. 1.12 Targeted campaigns drive increased participation in key citizen science opportunities. 1.13 A diverse cross section of the community is involved in the development of NRM policies and strategies. 1.14 Corporate volunteering and corporate skilled volunteering providing NRM agencies, not-for-profits and social enterprises with support to improve NRM. | 1.15 All sectors of the community actively caring for and participating in stewarding the environment. |

2. By 2040, there is increased participation of visitors and absentee landholders caring for and stewarding the natural environment across north east Victoria

| Medium-term outcomes | Established priority directions | Pathway priority directions | Transforming priority directions |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2.1 By 2027, an increase in the number of visitors actively involved in caring for the environment. 2.2 By 2027, an increase in the number of absentee landholders actively caring for the environment. | 2.3 Public land is managed to reduce visitor impact on high value natural environments. | 2.4 Damage to the natural environment by visitors is reduced through education and communication campaigns. 2.5 Increased skills and awareness of absentee landholders in how to steward their land and local natural environment. 2.6 Tourism providers and businesses supporting and funding or partnering in NRM activities across north east Victoria. | 2.7 Visitors actively caring for, taking responsibility and contributing financially to improve the health and condition of the natural environment. 2.8 Increased absentee landholder participation in or funding of land management activities to improve their land and local natural environment. 2.9 NRM integrated into theatre, TV, online resources, children’s books and tourism resources. |

3. By 2040, there is an increased diversity of investment in NRM in north east Victoria.

| Medium-term outcomes | Established priority directions | Pathway priority directions | Transforming priority directions |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3.1 By 2027, Landcare and community NRM groups are collaborating to secure region-wide investment in NRM. 3.2 By 2027, there is an increased involvement of the corporate sector in funding and creating solutions for NRM challenges. | 3.3 Locally based businesses consider impacts of their operations on the natural environment. 3.4 Locally based businesses offset their environmental impact. 3.5 Corporate social responsibility programs within the region targeted towards improving natural resources. | 3.6 Community-based Landcare and NRM groups supported to explore new investment opportunities. 3.7 Regional investment strategy developed to attract region-wide corporate and philanthropic investment in NRM. 3.8 Community based Landcare and NRM groups collaborating to secure region-wide investment in NRM. | 3.9 Recurrent funding secured and managed into perpetuity to provide community-based Landcare and NRM groups with resources to achieve region-wide improvements to natural resources. 3.10 Shared values programs with the corporate sector to establish funding models, provide new solutions and partner on NRM challenges. |

4. By 2040, Traditional Owner/First Nations Peoples knowledge and practice is adapted to a contemporary context and applied to plan for, heal and care for Country.

| Medium-term outcomes | Established priority directions | Pathway priority directions | Transforming priority directions |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4.1 By 2027, an increase in the number of formal partnership agreements between Traditional Owners and key NRM agencies. 4.2 By 2027, there is an increase in the number of projects/programs that incorporate and support the delivery of cultural objectives and priorities in Country plans and actions for each component area outlined in the Cultural Landscape Strategy. 4.3 By 2027, more Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples Victorians are employed to actively care for Country by creating culturally safe and inclusive workplaces, and through agency expenditure with Indigenous owned businesses. 4.4 By 2027, an increase in the number of programs, policies and strategies that are co-designed and implemented in partnership with, or led by, Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples. | 4.5 Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples co-design NRM strategies and programs with government agencies. 4.6 Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples undertaking assessments and developing cultural objectives to guide management of water, land and biodiversity. 4.7 Support for Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples to heal, apply cultural practices and build skills in conservation and land management. 4.8 Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples supported to reactivate systems of knowledge of practice and to develop and implement cultural indicators for Healthy Country assessment tools as part of reading Country. 4.9 Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples contracted to deliver on-ground components of NRM projects. | 4.10 Joint management of National Parks between Parks Victoria and Traditional Owner/First Nations Peoples. 4.11 Recognise and support cultural objectives of Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples in managing National Parks with Parks Victoria. 4.12 Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples co-designing structure of funding opportunities. 4.13 NRM agencies co-designing NRM projects for delivery with Traditional Owner/First Nations Peoples. 4.14 Where led by Traditional Owner/First Nations Peoples, Traditional Ecological Knowledge and scientific knowledge are shared to best manage natural resources. 4.15 Truth telling forum(s) for north east Victoria. | 4.16 Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples responsible for key NRM decisions. 4.17 Cultural covenant agreements between private landholders and Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples established providing access to private land for cultural practice, healing and connection. |