Vision

Our waterways are valued, healthy and adaptively managed; supporting environmental, cultural, recreational, and economic values

Introduction

A diverse network of regulated and unregulated rivers and associated streams and wetlands weave across north east Victoria. They link communities, industries and ecosystems and are highly valued.

Facts

- Region’s headwaters contribute 38% of the total water in the Murray Darling Basin, while representing only 2% of the land within the Basin.

- 10,602 km of designated waterways.

- 49,000 ha of wetlands.

- Five water storage areas with total capacity of over 7 million megalitres.

- 80% of the region classified as Special Water Supply Catchments.

- Seven hydro-electric power stations.

- 4% of the region’s surface water consumption currently occurs in urban areas.

Features

Water resources and surface water

North east Victoria has significant surface and groundwater resources and is an important water producing region, contributing 38% of the total water in the Murray-Darling Basin system, while representing only 2% of the land within the Basin.

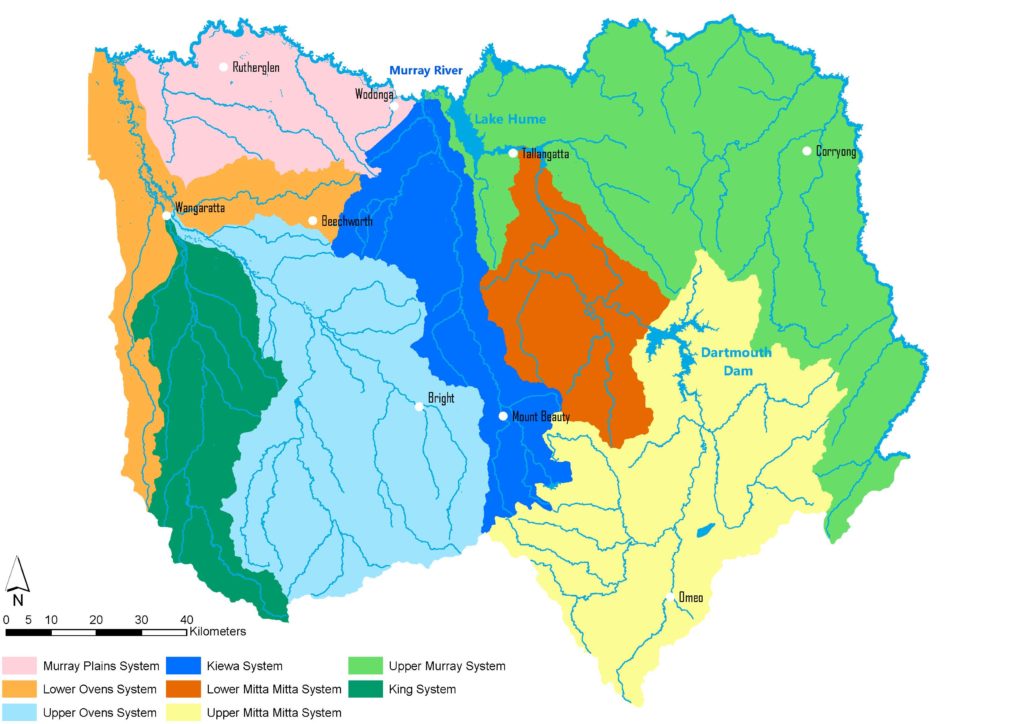

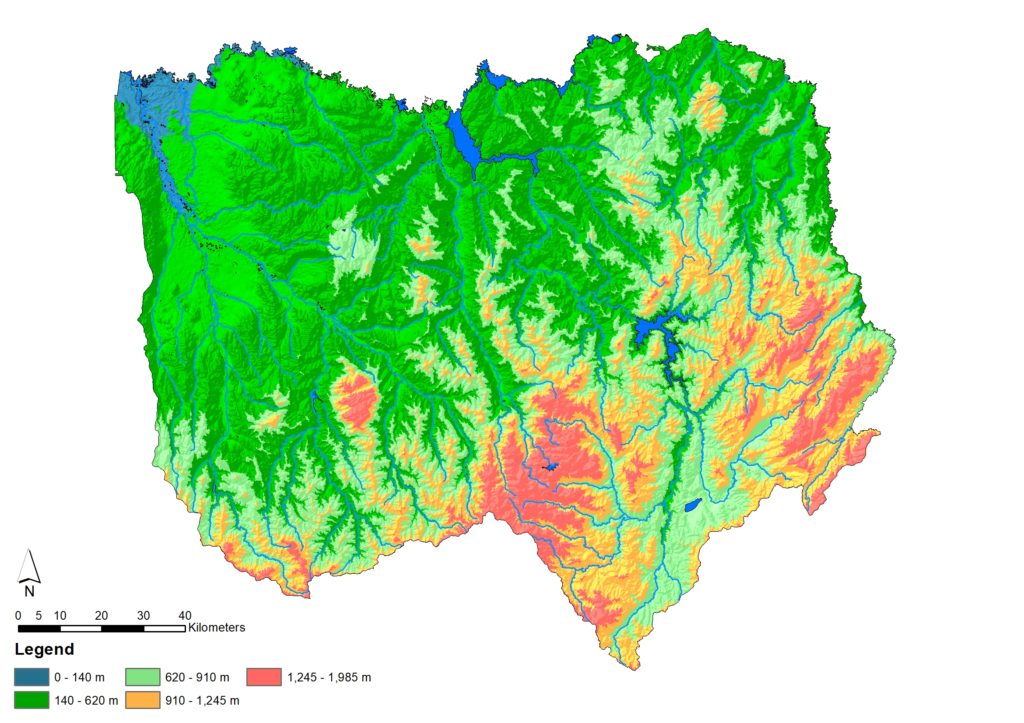

North east Victoria includes three major catchments: the Upper Murray, Kiewa and Ovens, which can be further divided into eight sub-catchment surface water systems as shown in Figure 1.

North east Victoria hosts several major surface water storages, including those described in Table 1.

| Storage | Capacity (ML) | Waterway catchment | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lake Dartmouth | 3,856,232 | Upper Mitta Mitta | Bulk water supplies for irrigation, hydroelectricity, domestic and stock and urban consumption |

| Lake Hume | 3,005,157 | Upper Murray | Reserve storage for bulk water supplies for hydroelectricity, irrigation, domestic and stock and urban consumption |

| Rocky Valley Reservoir | 28,400 | Kiewa River | Hydro-electricity generation |

| Lake Buffalo | 23,340 | Upper Ovens | Bulk water supplies for irrigation, domestic and stock and urban consumption |

| Lake William Hovell | 13,500 | King River | Bulk water supplies for irrigation, hydro-electricity, domestic, stock and urban consumption |

Wetlands

The total area of wetlands and wetland ecological vegetation classes in the region is approximately 49,000 ha on both public and private land.[17]

North east Victoria contains a variety of wetland types including freshwater meadows, shallow freshwater marshes, alpine wetlands, and riverine billabongs. The region also hosts nationally significant wetlands including Davies Plain and Mount Buffalo Peatlands, Lake Hume, Ryans Lagoon, Black Swamp, Lake Dartmouth, Mitta Mitta River and the Ovens River.

The lower Ovens River alone, downstream of Wangaratta, hosts over 1,800 wetlands.

The Alpine sphagnum bogs and associated fens (alpine peatlands) are unique ecosystems that are found in permanently wet sites in the alpine landscape. Alpine peatlands serve an important hydrological function as do the headwaters of the region’s major rivers, including the Murray River.

Floodplains

Floodplains and flooding are an essential part of ecosystem processes and supporting ecological and habitat values for native species. Floodplains also have fertile soils, laid down during periods of inundation, which make them sought after for farming.

While there are many benefits to natural flood events, they also impact negatively on the economic and social wellbeing of local communities.

Due to the steep nature of the landscape in north east Victoria, there are often only limited floodplain extents along many of the region’s waterways. Broad floodplains are restricted to the lower reaches of the major river systems including the Ovens River between Bright and the Murray, the King River downstream of Chestnut South, Fifteen Mile Creek upstream of Wangaratta and the Buffalo, Kiewa, Mitta Mitta and Murray Rivers. In the upper parts of north east Victoria, floodplains are generally confined and mostly contained within or closely surrounded by public land.

Groundwater

Aquifer and groundwater catchments do not follow CMA boundaries. Like surface water catchments, groundwater in north east Victoria has a northerly and westerly flow towards the Murray River.

- Most of the mid to upper catchments of north east Victoria have local groundwater systems that function in fractured rock aquifers in the hilly or mountainous areas of the Great Dividing Ranges. Groundwater depth in the elevated parts of the landscape is considered to be deep e.g. > 100 metres.

- Smaller localised groundwater systems also occur on the slopes in the valley floors.

- The larger groundwater systems, that have value as a groundwater resource for stock, domestic and agriculture, occur within the Riverine Plains landscape and within the larger floodplains along the upland rivers. The most significant aquifers occur in the Ovens and King valleys and extend from the Murray River south to the region of Greta, and from the Warby Ranges in the west to Springhurst and Everton in the east.

- Most of the region’s waterways are rated moderate to high for their potential to interact with groundwater. This interaction is particularly high in the Upper Ovens.

Water dependent species and communities

The region’s network of wetlands, floodplains, waterways and groundwater support many culturally significant, iconic, threatened species and communities. The biodiversity section of this RCS provides further background on water dependent species and communities.

Important attributes

North east Victoria’s community and visitors interact with water in the region for many reasons and hold shared and varying values. These values are further described in the local landscape sections. The following points describe the important attributes associated with water, identified by those who work, live, visit and connect with north east Victoria:

- Waterways, including protected headwaters, good water quality, flow variability and heritage and iconic rivers

- Surface water and groundwater availability for social, environmental and economic prosperity

- Connected floodplains and wetlands including nationally important wetlands such as Black Swamp, Ryan’s Lagoon and the Lower Ovens wetland complex

- Protected and vegetated areas along waterways providing corridors, habitat, shade and filtering function

- Culturally important, iconic and threatened water dependent species and communities

- Recreation, access and community connection to water is important.

Snapshot of condition

This section provides a snapshot of the condition of water in north east Victoria.

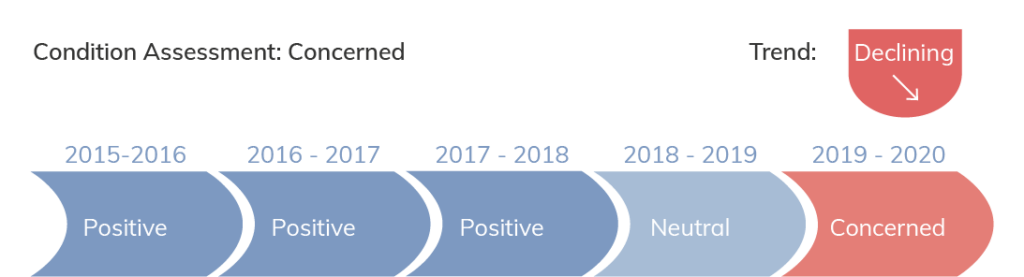

For the purpose of this RCS, the condition of water in the region has been assessed as of concern and in decline in 2019-20. The declining trend is predominately due to the impact of the 2019-20 bushfires that affected the health of waterways in the Upper Murray, Mitta Mitta and Ovens Catchments, by reducing water quality and increased erosion.

The condition assessment is informed by a range of indicators that are described further in this section. These include:

- Surface water

- Groundwater

- Wetlands

- Waterways

- Riparian and aquatic habitat

- Water quality.

Historical changes

For many thousands of years, the Country was managed and cared for by Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples. The water quality of the rivers and wetlands was largely unaffected by their presence.

In 1824, the Hume and Hovell expedition crossed the Ovens River at Whorouly, leading to the regional devastation of one of the oldest cultures in the world and marking the start of significant changes in the condition of Country. Governments gave land and water to European citizens, restricting Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples from access and use. Today very few Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples in Victoria own or manage ground or surface water entitlements.

From the 1850s to the 1930s there was a significant increase in population and with this increased land clearing, along with swamp and floodplain drainage. Gold mining also led to a huge increase in erosion and sediment ending up in our waterways. The Ovens and Mitta Mitta Rivers were particularly affected, with the valley floors incised by gullying and gold sluicing, flushing large amounts of sludge into the waterways.[18]

Many of the rivers in north east Victoria have also undergone extensive management interventions for over a century. This includes bank stabilisation, levees to confine flow within the channel, removal of native riparian vegetation and woody debris, and channel straightening and redirection. Despite ongoing management efforts, some like Nariel Creek have erosion problems that are far from resolved.

Surface Water

North east Victoria contains some of the most intact flow regimes across Victoria, water availability is good and the region is well known as a water producing region. This is because of the high and reliable rainfall, low development of dams and weirs in comparison to other regions and extensive areas of forest cover.

Catchment modelling work undertaken for the North East CMA, based on climate change models recommended by CSIRO, suggests there will be 20% decreases in surface flow to streams, deep drainage, and groundwater recharge by 2030, with a greater than 30% decrease by 2050. This has the potential to reduce water availability to both the region and the wider Murray-Darling Basin.

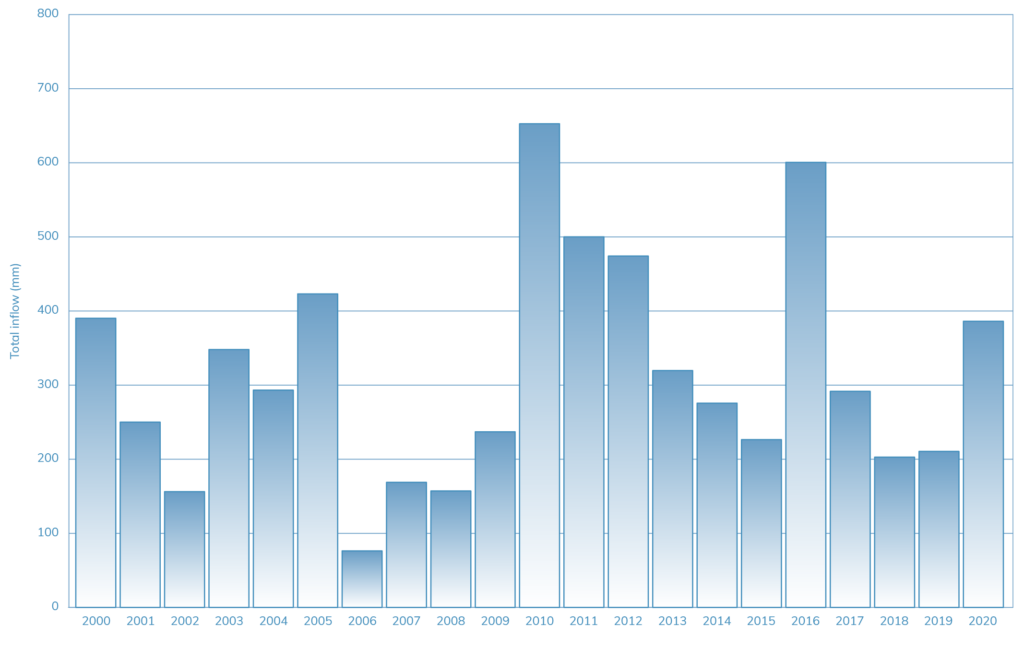

Over the past five years river inflows have been below the long-term average in four out of five years across the Ovens, Kiewa and Murray basins. Annual river inflows have been variable since the year 2000. National modelling undertaken by the Australian National University indicates the annual river inflows in north east Victoria’s waterways during 2019 was 210 mm, which was the second lowest recording since 2008, while in 2020, 386 mm was recorded, which is above the 20 year average.

Approximately 30% of snow cover has declined since 1954.[19] Future projections under a range of climate scenarios suggest snowfall will continue to decrease and that there will be accelerated snowmelt.

Groundwater

The stability or decline of groundwater systems depends on the amount of water recharging the system and on how much water is being used.

The following table summarises the general trends in groundwater levels in north east Victoria, based on analysis of the State Observation Bore Network (SOBN) for the Victorian Water Accounts annual reports 2014-19.[20]

The Lower Ovens area of the Ovens groundwater catchment was assessed to be declining in 2016, 2017 and 2019.

| Groundwater level trends (June) | Ovens groundwater catchment | Ovens groundwater catchment | Upper Murray groundwater catchment | Upper Murray groundwater catchment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper Ovens | Lower Ovens | Kiewa | Upper Murray | |

| 2014 | Stable | Stable | – | – |

| 2015 | Stable | Stable | – | – |

| 2016 | Stable | Declining | – | – |

| 2017 | Stable | Declining | Stable | Stable |

| 2018 | Stable | Stable | Stable | Stable |

| 2019 | Stable | Declining | Stable | Stable |

Wetlands

While north east Victoria hosts significant areas of Victoria’s most depleted wetland habitats, past water management and planning decisions have changed the course and flow of waterways and resulted in the loss of naturally occurring ephemeral wetlands.

More recently there is increasing pressure on wetlands from encroachment through agricultural and urban development which reduces the condition of these areas.

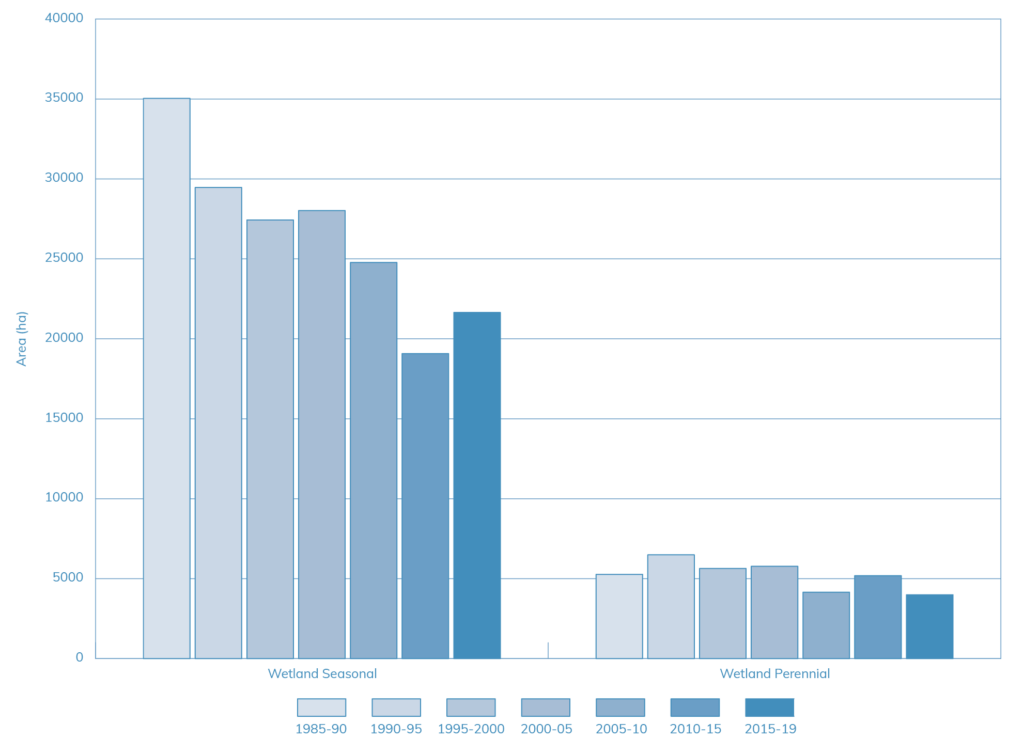

Seasonal wetland cover decreased by 38% from 1985 to 2019, while areas defined as wetland perennial, have decreased by 24% over the same period.

Waterways

In 2010, waterways within north east Victoria were considered in good to excellent condition, as measured by the Index of Stream Condition. Since 2010, land use changes and events including drought, major bushfires in 2012 and 2019-20 and major floods in 2010, 2012 and 2016 have impacted on the health of waterways and wetlands.

By 2017, 56% of total waterway length in the region was in moderate, poor or very poor condition.[21]

Riparian and aquatic habitat

Riparian vegetation and aquatic habitat play a crucial role in waterway health and biodiversity.

With 55% of the region permanently protected by public land, large lengths of waterways are in forested areas. Riparian vegetation in valleys that are dominated by agriculture have less connected stretches of riparian vegetation. Figures to quantify the proportion of waterways protected by riparian vegetation or fencing are currently unavailable for north east Victoria.

In-stream woody habitat (IWH) includes the snags, trees, branches and logs that are found in rivers and streams. IWH is essential for maintaining health of a waterway. Its removal is a major factor contributing to the decline of many freshwater fish populations.

IWH condition in north east Victoria is comparatively better than other parts of the state. IWH condition in most of the Upper Murray system and parts of the Kiewa and are in excellent condition showing only minor variations from natural IWH. In contrast, the Murray Plains is in poor condition with IWH severely (> 80% decrease) or highly depleted (60% to 80% decrease) in several rivers. Depletion of IWH is also recorded in parts of the Lower Ovens, Upper Ovens and Upper Mitta Mitta systems.[22]

A range of activities delivered by the community and agencies contribute to habitat improvement and long-term improvements in the condition of waterways. Activities such as fencing and troughs for off-stream watering, revegetation and weed control, all support improved riparian and aquatic habitat and waterway condition. Table 3 provides a summary of waterway and habitat improvement activities that were supported by North East CMA in partnership with community and other stakeholders, between 2016-17 and 2019-20 in riparian areas and waterways.

| Outputs/Year | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structural works | Fence (km) | 31.4 | 29 | 29 | 27 |

| Water Storage – trough (no.) | |||||

| Waterway structure (no.) | |||||

| Environmental works | Vegetation (ha) | 74.4 | 154 | 144 | 144 |

| Weed control (ha) | 318.3 | 623 | 613 | 588 | |

| Planning and regulation | Management agreement (no.) | 10 | 57 | 57 | 57 |

in north east Victoria.

Water quality

North east Victoria contains some of the highest water quality in the State. Objectives and indicators for water quality are outlined in the Victorian Government’s State Environment Protection Policy (Water). Attainment against these measures was reported in the 2018 State of the Environment report, which showed overall water quality across the region varied from moderate to excellent with most areas in good condition (Table 4).[30]

| Water Quality Indicator | Attainment of SEPP 2010-17 |

|---|---|

| Dissolved Oxygen | Excellent |

| Salinity | Excellent |

| Total Nitrogen | Good |

| Total Phosphorus | Moderate |

| Turbidity | Moderate |

| pH | Excellent |

Trends in water quality vary across the region and are dependent on a range of factors including land use and management. Stock access to waterways continues to impact on water quality across north east Victoria and effluent from dairy farms has also caused water quality concerns in recent years.

Urban stormwater runoff is an emerging issue for north east Victoria, with more urban development, resulting in some areas becoming increasingly impervious. These hard surfaces have a decreased ability to absorb water, resulting in changed stormwater drainage and associated impacts on in-stream ecological condition, reduced contribution to baseflows and increased frequency of magnitude of storm flows.

The Border Mail (2020) [24]

Please note, this ‘snapshot of condition’ does not incorporate assessments of Healthy Country by Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples. Throughout the RCS renewal and implementation, we are committed to working with Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples to restore and protect Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples knowledge systems and to integrate Healthy Country Assessments into monitoring and evaluation processes; acknowledging that traditional ecological knowledge and indigenous knowledge and practice will be protected under the authority of each Traditional Owners/First Nations custodian and group.

What is changing?

The world and our region are rapidly changing and our region is more interconnected across multiple spatial scales than ever before.

The fundamental drivers of change described in the Our Region – What is changing? section influence all systems and landscapes in north east Victoria.

Table 5 provides additional changes and specific insights into what this means for water in the region.

| Driver of change | Leading to |

|---|---|

| Climate change | Hotter and drier climate and longer and more frequent drier periods leading to reduced streamflow. Droughts are likely to increase in frequency and can lead to loss of riparian vegetation, enhanced bank erosion and reduction in water quality. Decline in snow fall and average rainfall leading to reduced groundwater recharge and streamflow. Declining average rainfall and change in seasonal patterns – decrease in modelled water yield of up to 30% less water by 2050 and less rainfall in autumn, winter and spring. Longer and more frequent drier periods leading to reduced stream base flow and impacts for water quality such as low oxygen events, fish kills and blue-green algae blooms. Wastewater infrastructure is vulnerable to disruptions and increasing costs of energy supply. Increase in scarcity and demand for water resources between competing potable, agricultural, environmental, and cultural uses. Transfer of water and increased demand for water outside the catchment. |

| Growth and changes in land use | Increase in irrigation development and urbanisation, which increase water demands and impacts on water quality and run-off. Urbanisation and urban growth increasing the extent of impervious surfaces and changing run-off regimes. Increase in the impact of urban stormwater on water quality through increased nutrients and pollutants. Land use pressures on declared water supply catchments and wetlands such as Black Swamp and Ryan’s Lagoon. Increase in urban and peri-urban development encroaching into riparian and floodplain areas. Pressure on off-grid water services and wastewater treatment. Interest in water sensitive urban design (WSUD) approaches is growing. |

| Water market is maturing | Potential for the Ovens regulated system to enable water trade to other regulated systems. Water moving to those who can pay and the highest value commodities. Potential uptake of sleeper “unused” groundwater licenses in the Ovens, King and Kiewa catchments putting pressure on waterways and ecologically valuable Ovens floodplain. Increased irrigation development in the Riverina Lower Ovens Landscape. |

| Increase in visitation and recreational use of water resources | Increase in the visitor numbers for a range of water-based activities, including fishing, boating, kayaking, rafting and water sports. Increase in the pressure and demand to access riparian areas, waterways and increased access to fishing and camping on crown land with grazing licences and river frontages. Improvements to developments and amenities around waterways and water storages. Increase in visitation and use putting pressure on waterways and riparian areas, leading to bed and bank erosion, impacts on aquatic fauna, the introduction of weeds, reduced water quality and litter. Increase in volunteer projects for waterways and investments from recreational fishing license fees. |

| Acute Shocks | Fires were followed by rainfall leading to enhanced bank erosion, poor water quality, and increased risk of channel course changes. As forests re-grow in the recovery from major fires, there is likely to be a reduction in run-off from these catchments. Droughts are likely to increase in frequency and lead to loss of riparian vegetation, enhanced bank erosion and reduction in water quality. |

| Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples rights | Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples expressing the right to be included in the decision-making of water allocation and planning processes. Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples are increasingly influencing NRM strategies, stream flow management and undertaking environmental works prioritisations. For example, in June 2019, 39 ML of water owned by Taungurung Land and Waters Council was donated to enhance the flow of the King River. |

| Changing management and governance | Responsibilities for the protection of the environment have changed through the General Environmental Duty. There will be an increased onus on individuals and organisations to manage activities to avoid the risk of environmental damage to waterways from pollution such as dairy effluent. |

Resilience insights

The changes described in the section above, directly impact the water system in north east Victoria.

To build the resilience of the water system we need to understand if these changes are strengthening or reducing the resilience of water and thresholds. Thresholds are known limits for characteristics of water that, if reached, trigger a change in water and its critical attributes.

Often thresholds are based on western science and quantitative data. Thresholds in this strategy include consideration of available science, data, traditional ecological knowledge and community knowledge.

In many cases, there is insufficient knowledge or data to determine thresholds. We will continue to work to build understanding and knowledge of thresholds during the life of the RCS. Consideration of these thresholds will be considered in the development of the detailed monitoring and evaluation plan for the strategy.

| Factors strengthening resilience | Factors reducing resilience | Threshold |

|---|---|---|

| Waterway connectivity by reducing barriers to flow and diversity of channel form. Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples caring for Country and integration of Traditional Ecological Knowledge. A strong and connected network of Landcare, community groups and communities caring for waterways. Strong history of collaboration in managing water challenges and a drive for research, new approaches and innovation. Water licences that are not currently active providing additional environmental water to waterway systems. High reliability of surface water. Considerable investment into aquatic fauna surveys and specific water focused research. Landholders and managers practicing catchment stewardship and considering integrated catchment management. Traditional Owner/First Nations Peoples healing knowledge and country and increasingly involved in managing and governing country. Updated Irrigation Development Guidelines for the region, guiding irrigation development decisions. | Urbanisation and associated degradation of waterways. Excess stormwater runoff leading to water, nutrients and pollutants entering waterways. Artificial structures in waterways (weirs, barriers, rip rap etc.) that impact on natural flows of water and fauna. Groundwater pumping can impact on groundwater discharging to stream, wetlands and springs and decrease availability. Complex and difficult to understand systems of water allocation and trading. Water allocation strategies and policies not considering impact of climate change and water availability into the future. Large movement of allocated water out of north east Victoria for downstream users. Increased irrigation extractions reducing redundancy. The perception that there is not enough water to meet ecological needs and to support highly valued ecological processes. Climate variability with extreme weather events becoming more often and intense, leading to less time to recover. Absence of water quality monitoring to predict major water quality events. Resistance from some parts of the community to restricting stock access to waterways and revegetating riparian areas. Communities and agencies ill-prepared and informed for activities to secure safe water and prevent water quality issues post extreme events. Limited involvement of Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples in water markets. | Directly connected impervious (DCI) area > 2% in urban areas. Water quality parameters meet the relevant SEPP (WoV) environmental quality indicators: * 80% of water quality parameters within SEPP tolerance limits 100% of the times * No algal blooms in water storages * Dissolved oxygen is above 5mg/l 100% of the time in streams with natural/self-sustaining populations native fish 20 metre riparian zones on a stream or wetland, (noting 30m is best practice). Redgum floodplain inundation: not continually dry for >3 years No greater than 3 years without a spring fresh. High priority wetlands do not exceed wetting/drying cycle tolerances. Greater than 5% uptake of existing “sleeper” licences across the region. No year without an increase in area subject to cultural practice. |

Outcomes and priority directions

Vision (By 2050)

Our waterways are valued, healthy and adaptively managed; supporting environmental, cultural, recreational, and economic values

The table below describes the course we will take to move towards our vision for water by providing:

Long-term outcome – these describe where we want to be in 20 years

Medium-term outcomes – these describe what we are currently doing and where we want to be in six years and help us to measure success in moving towards our vision and long-term outcomes

Established priority directions – what we are currently doing and want to continue to do over the next six years. They will help us build resilience in the face of change. Many of these directions are about persisting and adapting to change.

Pathway priority directions – ways forward over the next six years, that are not currently common practice in the region. They will help us adapt to change and are bridging activities between the current way of doing things to moving to a fundamental change.

Transforming priority directions – new practices that create a new way of doing things, that will be investigated, and where feasible implemented over the next six years or outside the lifetime of this RCS.

We will implement all three priority directions, Existing, Pathway and Transforming, to achieve our vision.

It is also recognised there is a need for a shift in current approaches to planning and management paradigms, so that Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples can heal Country and culture, through application of cultural knowledge and practice. This will take time. Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples will guide the process using the Traditional Owners Strategic Framework for Managing Country outlined in the Victorian Traditional Owners Cultural Landscapes Strategy

1. By 2040, regional growth will create more liveable and water sensitive regional cities, centres and towns

| Medium-term outcomes | Established priority directions | Pathway priority directions | Transforming priority directions |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 By 2025, appropriate amendments are made in local planning schemes to include provisions and targets for management of stormwater. 1.2 By 2025, all growing regional cities, regional centres and towns are transitioning to becoming water sensitive, demonstrated through an increase in their water sensitive city rating. 1.3 By 2027, water-sensitive urban design (WSUD) has been implemented in all new developments. 1.4 By 2027, priority areas for retrofitting of WSUD in developments that have occurred within the period 2011 to 2021 have been identified. 1.5 By 2027, retrofitting of WSUD in developments that have occurred within the period 2011 to 2021 has been demonstrated in five priority areas. | 1.6 Assessments undertaken to determine the water sensitivity of growing regional centres and towns and a baseline established. 1.7 North East Integrated Water Management (IWM) Forum is supported to develop programs and place-based IWM plans for agreed priority locations. 1.8 Implementing WSUD including stormwater capture and reuse treatment is achieved through local planning schemes. 1.9 Continue to build capacity to implement WSUD by establishing WSUD demonstration projects, preparation of guidelines and educational programs. 1.10 Exploration of the use of fit-for-purpose alternative water sources for irrigation of community green/blue spaces, industry and other uses. | 1.11 Agencies and local government supported to achieve water sensitive city targets. 1.12 Explore and prepare a business case and method to determine appropriate planning provisions and targets for stormwater management such as Directly Connected Imperviousness (DCI) percentage for north east Victoria. 1.13 Implement and enforce planning scheme outcomes. 1.14 WSUD is implemented in a way that promotes achievement of multiple outcomes, including public amenity, habitat protection, reduced water use, reduced energy use and are low maintenance. 1.15 Integrated water management is embedded in regional and local planning strategies and action plans. 1.16 Water sensitive plantings are promoted in open green/blue spaces and low-water gardens in private homes. | 1.17 WSUD is implemented as part of a wider Water Sensitive City transition plan for all local government areas within north east Victoria. 1.18 Fit-for-purpose, alternative water for community green and blue spaces, industry and other uses is maximised. |

2. By 2040, north east Victoria’s communities and industries continue to adapt to a future with less water due to reduced inflows from climatic changes, allowing for water to maintain environmental, cultural and recreational values

| Medium-term outcomes | Established priority directions | Pathway priority directions | Transforming priority directions |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2.1 By 2027, the Northern Sustainable Water Strategy, Murray-Darling Basin Plan and regional strategies include consideration of the impact of climate change and land use change in water requirements for north east Victoria in downstream water entitlements. 2.2 By 2027, there is an increased number of participants involved in programs that increase adaptation to reduced water availability. | 2.3 Input into State and Federal policy and planning processes to improve and protect the environmental water resources across north east Victoria. 2.4 Seasonal watering proposals are developed for environmental water entitlements to maximise ecological objectives, as well as the shared benefits. 2.5 The timing and quantity of extractions from waterbodies, waterways and groundwater is managed to provide for human/industry needs, while minimising the impacts on the aquatic environment. 2.6 Incentives and extension support for irrigated agriculture to improve water use efficiency. 2.7 Groundwater management plans are reviewed and updated. | 2.8 Improved understanding of the implications of climate change, changing land use and bushfires on surface and groundwater dynamics is built into strategies and plans. 2.9 Support improved community understanding and transparent communication of how water is managed, used and maintained for environmental, cultural and recreational values. 2.10 Ensure water use in unregulated waterways is within ecologically acceptable limits, both now and under a range of climate change scenarios. 2.11 Communities understand and are supported to plan for a future with reduced water availability due to climate change. 2.12 Promote the value of the 38% of Murray-Darling Basin water provided by north east Victoria for downstream users and the need to protect the quality of this water and water availability for north east Victoria. 2.13 Recreational access that is compatible with social and environmental values. | 2.14 Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples own, utilise or deliver water to support cultural values and practices. 2.15 Regional communities have adapted to a future with less water. 2.16 Existing water markets are utilised to achieve cultural and environmental outcomes through underutilised water. 2.17 Industry and agriculture have diverse water options to provide redundancy during times of low water availability or poor water quality. |

3. By 2040 waterways are healthy and well managed thereby protecting waterway dependent iconic, culturally important and threatened (priority species) species

| Medium-term outcomes | Established priority directions | Pathway priority directions | Transforming priority directions |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3.1 By 2027, 100% of priority waterway reaches show an increase in the extent (ha) of improved or protected riparian zones. 3.2 By 2027, the extent (ha) of perennial and seasonal wetlands has not decreased from the 2015-19 extent (25,638 ha) and there is improved connectivity. 3.3 By 2027, in-stream woody habitat has been improved in 50% of priority waterways. 3.4 By 2027, there is an increased number of projects/programs that incorporate and deliver on Aboriginal water assessments and Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples cultural objectives. | 3.5 Partnerships in place between government and community to fence and revegetate riparian areas and wetlands. 3.6 Implement regional waterway strategy priority activities. 3.7 Fund and support Aboriginal waterway assessments. 3.8 Renew and implement the North East Regional Waterway Strategy. 3.9 Programs to raise awareness of and implement the General Environmental Duty under the Environment Protection Act 2017. | 3.10 Investigation and understanding of high value wetlands and opportunities to increase connectivity. 3.11 Support and invest in the integration of Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples cultural practices into the management of waterways and wetlands. 3.12 Additional stewardship partnerships between government, landholders and Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples for active management of riparian areas and wetlands e.g. rate rebates, annual management payments, co-management arrangements. 3.13 Increase in understanding and education of waterway/wetland management and use and impact on priority species. 3.14 Support and invest in Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples developing indicators and assessment tools for monitoring culturally important species and values. 3.15 Increase in riparian management activities to reduce pollutants and sediment from entering waterways following extreme events. 3.16 Watering of high value wetlands that require increased connections. | 3.17 The quality of water is managed to meet State and Murray-Darling Basin agreed standards and targets 100% of the time. 3.18 No artificial structures that provide an impediment fish passage in north east Victoria’s waterways. |

4. By 2040, there is improved protection of water quality and waterway/wetland/floodplain system values during and following extreme events

| Medium-term outcomes | Established priority directions | Pathway priority directions | Transforming priority directions |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4.1 By 2027, the location of waterway drought refuges for aquatic species across the region is known and their protection has improved. 4.2 By 2027, cross sector collaborative plans are in place to protect water quality during extreme events. 4.3 By 2027, there is an increase in riparian activities including fencing, off-stream watering and revegetation to protect waterways from extreme events. 4.4 By 2027, there is an awareness and readiness for action for blue green algae events including small events on farms and larger regional events. | 4.5 Research into the location of drought refuges in waterways. 4.6 Water quality education and extension during fire recovery. 4.7 Waterway works to support recovery post fire and flood funded and implemented. 4.8 Potable water testing and water testing in storages to advise communities of water quality issues and risks. 4.9 Water quality testing in waterways during recovery from fires to inform species rescue requirements. 4.10 Water monitoring and awareness that identifies blue green algae in farm dams and other water systems. 4.11 Stewardship by land managers and incentives to protect riparian areas including fencing, revegetation and off-stream watering. 4.12 Implementation of North East Floodplain Management Strategy. | 4.13 Waterway drought refuges for aquatic species are identified and mapped. 4.14 High level response plans developed for waterway health to outline measures that should be considered during fire response and recovery. 4.15 Materials developed for extreme event communication and education around water quality protection during recovery. 4.16 Early predictive online monitoring to predict major water quality events. 4.17 Establishment of a cross border/interagency plan to prevent, respond and monitor regional blue green algae events. 4.18 Identification of triggers and encouragement of the adoption of appropriate responses to small on- farm blue green algae events. 4.19 All emergency management partners and teams understand best practice responses to protect water quality and waterway/wetland and floodplain systems during emergency events. 4.20 Plans in place for farms and industry to access safe water following emergency events. 4.21 Support Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples led water quality monitoring programs and the development of culturally informed ‘healthy water indicators’ 4.22 Cross agency, community and Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples water quality monitoring partnerships. | 4.23 Waterway drought refuges for aquatic species protected and enhanced through agencies/landholder partnerships. 4.24 90% of riparian land is protected from stock access. 4.25 Sufficient environmental water is held to ameliorate poor water quality and provide aquatic refuge during and after extreme events in regulated systems. |